Matt Blackwell

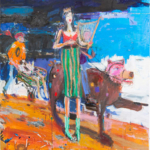

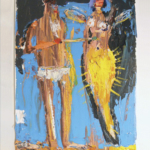

A black bear hoists a flag in the midst of a beachfront procession. Aloft the flag exhibits a red asterisk as its emblem. Or another, different bear. This time serenaded by a young woman on her ukulele as the bear presents a gargantuan, yellow daisy bouquet. The serenading girl is seated upon an improvised seat of concrete blocks. The dwelling behind her is a large pumpkin house. A stovepipe ascends, aspirationally high, above the orange roofline. Or, now another painting, and yet another bear, with a smaller bouquet of smaller daisies. The bear hides behind a woman in a checkered dress while she blasts her machine gun out of frame at unseen threats.

Matt Blackwell has had a long running dalliance with bears in his studio. They are in his paintings, his sculpture, drawings and prints. But if this bear of Blackwell’s is a motif, an iconic presence in his work, then it needs be seen as a very particular bear. This is the bear with a thousand-yard stare, the bear that has seen way too much of human culture in small upstate New York towns. It has seen way too much of suburbia, exurbia and all manner of built human sprawl. This bear has spent too many twilight evenings digging through dumpsters at the local KentuckyfriedMcTacobucks. These animals that he depicts, sometimes roughly, sometimes in tender descriptive detail, evoke a tutelary presence in his fictional world but also they are sometimes just people’s pals, buds. Importantly, Blackwell stands his bears up. He presents Caniformia —dog-like— creatures as bipeds. These are then creatures that have evolved across the territory of upstate New York and the time of Blackwell’s studio practice into something akin to humans. These are bears that marry totemism to an inter-species social milieu spawned in the drift of dying upstate New York.

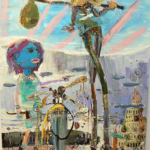

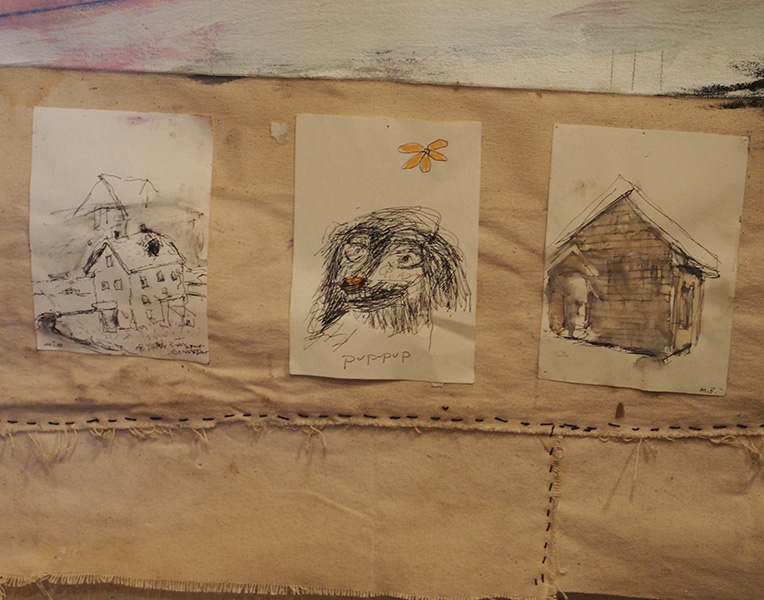

American vernacular culture, with a deep past adrift in the ruins of the present, shades the work. In turn, the work is populated by a whole range of character types, from guitar pickers to deer hunters and hitchhikers, any of whom might sometimes be found facing off against or canoodling with the aforementioned bears. These characters (and the feeling is very much that they are characters in an almost theatrical even picaresque sense) are frequently finding their lives juxtaposed —visually, on the canvas’ surface— with muscle cars, splatters of unruly paint and Bob Dylan quotes. Often the whole is staged in a setting of raised ranch houses and something that resembles the ‘back forty’ of Palookaville.

A recent Guggenheim award allowed Blackwell to travel, to spend time in and produce work in both the Southwest of the United States where he currently has family, and also in his native upstate New York. Even before the grant Blackwell was something of a regionalist chronicler. As such the paintings are a form of notation or witnessing. But if the footing is in regionalism there is also a Hogarthian cocked eye on the lookout for the right scene that will give us regionalism’s crusty experience as a cautionary lesson for the wider world. Throughout his practice Blackwell cleaves to a wary sense of the flattening out of distinct cultures around the nation-wide litter of the supply-side economic disaster imposed upon much of the country in the last three-plus decades.

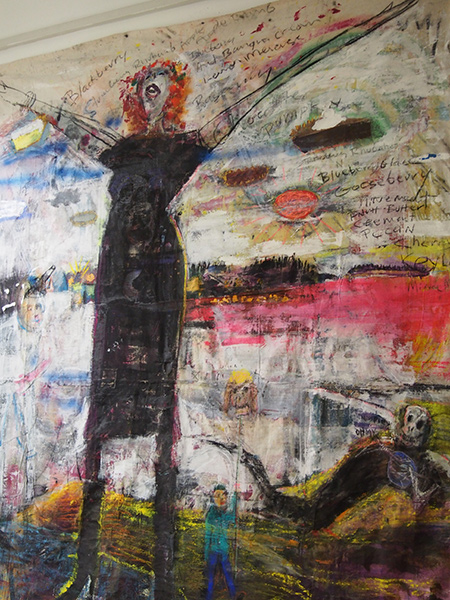

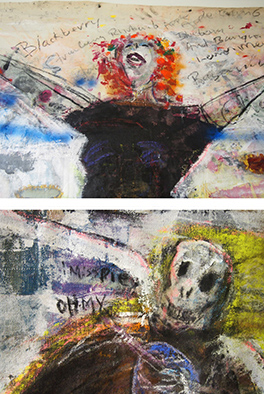

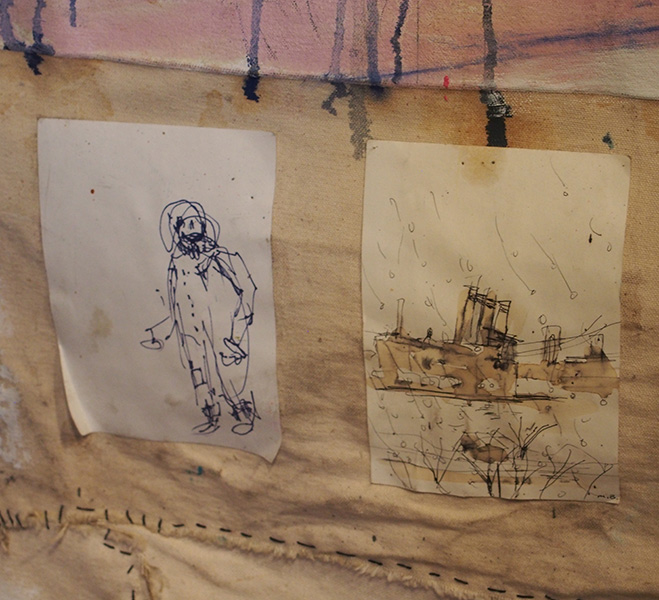

Blackwell’s bears are witness to all this through an idiosyncratic expressionistic, reportage style. One could think of him as a dreaming witness. As a viewer, you address a Blackwell painting and a tangle of color and texture comes to meet you. Often it looks like Blackwell has been through a gladiatorial brawl with paint and brush. Smoldering images combust out of seemingly disorganized globs and slashes of paint. There are levels of messy delight in abstract color or texture long before, and after, one arrives at the recognizable image. His pictorial rhetoric, his reportage, does not so much weave between these expressive jags of paint, rather it drags them, very forcefully, into the document-like stains of authorship (or confusion and horror) on the reporter’s notebook. Through this Blackwell’s translation of quotidian experiences and objects –pie, car, canoe, even bear– transubstantiates them. He imbues them with a profane vibration. Enters them for consideration as the codex of this provincial life-world of upstate New York.

AN EXAMPLE As is often the case with Blackwell, Bear Trouble (2001–2002) is a crowded painting; which is to say, the decks have not been cleared. The yellow glare of a candle illuminates with a preposterous power, embalming half the painting in its aura. The shadows it creates monsterize the woman as she faces the viewer. Her arms akimbo, the right hand comes to rest on a giant plush red heart. The spacing of the bear and the woman opens up and triangulates to include the viewer. Indeed having the viewer at hand (like a spectator to a private scene) seems to assure that there is a clear narrative transaction around desire and lust to be found in the painting. Stripes spring out from the candle, running along the bed-come-couch to bar the space between the two characters. The feint of seduction is offered but the bear looks slightly sideways, all but acknowledging the viewer, perhaps embarrassed by his perceived un-lust. Another, minor glow, rendered differently, above the waistband of his underpants licenses his blush. Desire displaced, a very particular interiority revealed: pie!

Importantly pie is, for Blackwell, a motif almost as recurrent as bears. For him pie is always declarative, rather than simply the label “pie.” Pie is productive, it brings forth embedded context. This is pie as it is found in upstate diners. It is the sign of earned recreation, almost luxury. This is allegorical pie. The pie of formerly prosperous white working-class Americans driving down-at-heels Cadillacs up the Adirondack Northway. This is the same pie that appears in Blackwell’s sculpture, Bear and Pie (2009). Extruded this time from the north of the body rather than ingested in its south. Pie is heavily overdetermined as an interior proposition to oneself per reward and a semiotic transaction among obedient consumers. For Blackwell it is a sign of the enhancement of life, almost it’s edification. But it is also a channel to enhance erotic and gustatory sensation.

It is pretty much routinely the case that Blackwell’s sculpture is fabricated from found materials, often discarded trash. Blackwell favors tin ceiling material held together by very visible rivets and caulk. Edges are ragged and sharp, these are dangerous looking objects. When the work is fresh in the studio one is surrounded by the odor of toxic silicone; perhaps for Blackwell it is something like the smell of napalm in the morning. If so this would be Blackwell’s triumph over the trash scattered across the back forty rendered in so many of his own paintings. However, he recycles junk not as a green strategy, rather this is as a man simultaneously flailing at and harvesting the discarded clutter of upstate New York. In this there is an ongoing conversation back and forth between the painting of junk and the junk of sculpture. Thus a junk object that evokes for him a metonymic connection, something as simple as ‘this looks like a face’, will become a face in a sculpture. Or, as in the painting Flinty Pilgrim (2006–2007), the eponymous figure wears a back-turned saucepan as a hat. The same actual saucepan is hiding in plain sight in the sculpture Load (2015).

Mired in geography and travels as Blackwell is, he knows that said geography –upstate New York, the trips to the Southwest– beget roads. And while the New York Throughway has featured prominently in at least one of his paintings, it is the sense of ambling, aimlessly traveling along some loosely described anonymous road, that most characterizes the work. Blackwell’s characters are perpetually on a road to somewhere, or, Ken Kesey’s smart-alecky take, they might be going “Further.”

Any number of the characters Blackwell paints appear as, if not actual hitchhikers, then as people paused, stalled, by the side of some road waiting for a ride. In Viva, (2012) a woman stands tall with a hat or ‘do’ that turbans her head like a model ordnance explosion. Her gaze looks out of frame past the viewer, down the road eying for an approaching something. Barely described, almost cropped out of the painting to the left, is a greyish suggestion of a Holiday Inn sign. Behind her the yellow sky fades toward an empty distance. The landscape feels more Western than upstate. To her right, at head height, a greyish yellow rectangle is captured by a darker yellow-orange circular line. The sky is bright, save for a dark grey swab of a cloud above her head. The grey rectangle formally rhymes with the woman’s head, while the cloud is assuredly hers, not its.

It seems possibly that there was some intent to paint a second character alongside the woman, the ghostly circle and square being all that remains of a changed mind or a lack of time or interest. Quite what Blackwell poses her as waiting for is an open question. A ride perhaps, or some more ethereal visitation: the Grove City bus or a Damascene apparition? And, if we suppose it is not the road to Damascus in Viva, then Blackwell is trafficking among a crowded set of alternate references. He trades off a dialogue between the rendered woman’s confrontation with the desolation of the empty landscape and the painter’s confrontation with the desolation of an empty modernist sign –that grey rectangle. This latter being exactly the kind of painting device he has had little use for in his studio time. What Blackwell really hankers for is a mode of narration. He needs its momentum. Whether he is thinking of Albuquerque, Malevich or even Caravaggio’s St Paul (come to that), in doing so he begs and borrows from any and all such references. Usually the feel for the viewer is that Blackwell moves fast, urgently working to tell the story. The paintings are almost always choc full of marks, references, narrative incidents, allusive signs, images hidden behind other images. And in Blackwell’s dreamtime juxtapositions we might not be surprised to find a Holiday Inn along the historical route of St Paul.

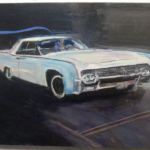

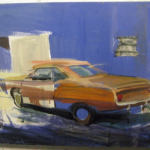

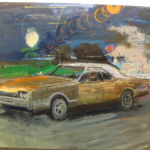

And if roads beget buses and hitch hikers, and can become vehicles for art historical juggling, they can assuredly coax cars onto the scene. Muscle cars of 1970s vintage are something of a sub-genre of Blackwell’s. Lingering in uncertain landscapes they pose for mournful portraits upon bare, often sewn together sections of linen canvas. The celebration is often times of their past glory, with an emphasis on past. Their current decay is very evident. The rust, the dings, the scratches and the miss-matched repair jobs are tenderly rendered as signs of history unfolding. They are staged on speedily rendered roadways or stalled on the back acre surrounded by litter and junk that reads as the repository of changing cultural desires. The decay itself is neither valorized nor judged. It is taken, rather, as a mandatory condition of their life. It is a condition they age into as the decades crank by and the money to restore classic cars eludes their owners. It is inbuilt obsolescence for those who cannot afford it. These, usually large paintings, seem like impossible, plangent hallucinations of recent history that promised but barely delivered. These are images that do indeed resonate with the regionalist chronicle, but also they narrate Detroit’s —well, the broader commodity culture really— lures and the catastrophic reality of how that detonated around those who were lured.

These scenes, objects and props Blackwell stages for his protagonists are vehicles for affect. A culture of an all but bereaved class and region parades through his studio. In Blackwell’s characters, glancing out toward us as they so often do, there is a sense of what sometimes seems like idleness. Or, it is perhaps something more menacing that the artist is recalling with his scenes from upstate. It is a stifled or denied sense of agency for people who more or less went along for the supply-side ride.

http://mattblackwellstudio.com https://www.edwardthorpgallery.com/matt-blackwell

happy to see into studio of matt blackwell – such a wonderful painter + those scrapy sculptures, oh my.

This is so well written a pleasure to read and full of fresh insights. I love Matts work he tells a story with paint and also

Enlists all manner of discarded junk to form fee standing characters great ro have all these pictures to see the full range.

Fantastic work . Beautiful essay. Saw Matt show at the Portland museum and was blown away. This guy deserves more attention .

terrific essay, smart work