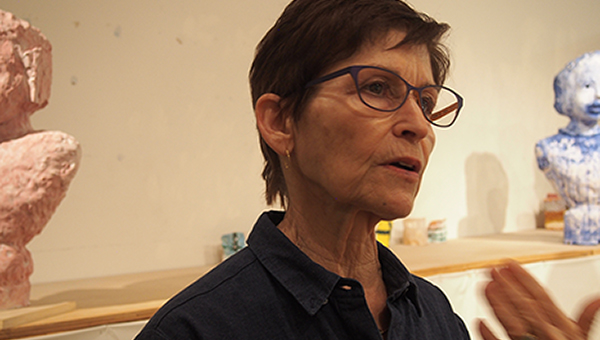

Barbara Campbell Thomas

The devices of Modernism are relentless, they are everywhere, They just won’t go away. And if they are not really there we project them anyway.

Barbara Campbell Thomas’ studio is near Greensboro, North Carolina (not so far, as it happens, from Black Mountain College, where many a modernist device was refined). The studio is in a separate building set back from the house she shares with her family. The living of family life, of parenting and of teaching at University of North Carolina, Greensboro, sets the cadence to and informs the time spent in the studio. Painting is thus a practice that must be shaped into the demands and experiences of those other aspects of her life. Crucially there is a trafficking back and forth between the various areas of her life. Boundaries are negotiable, border crossings frequent.

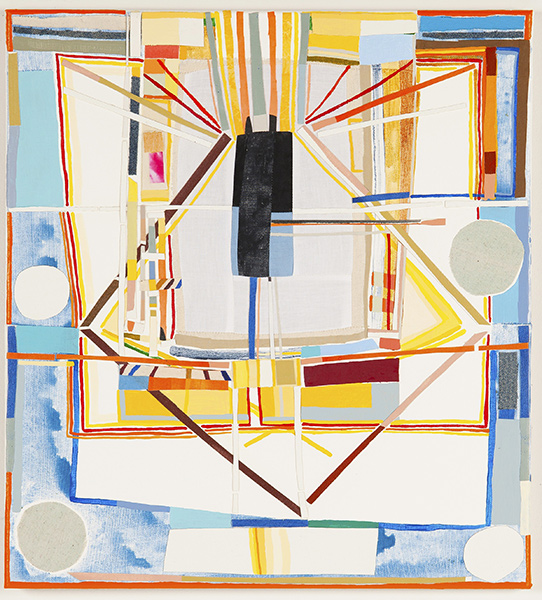

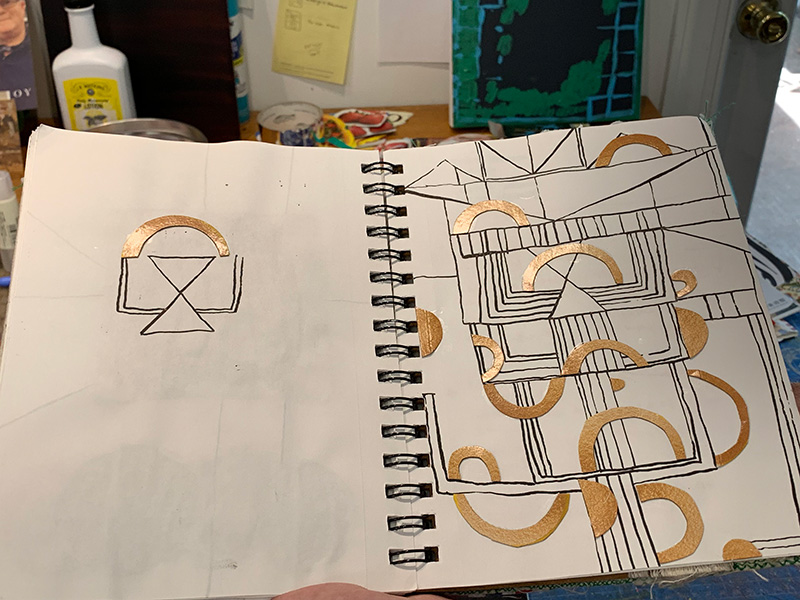

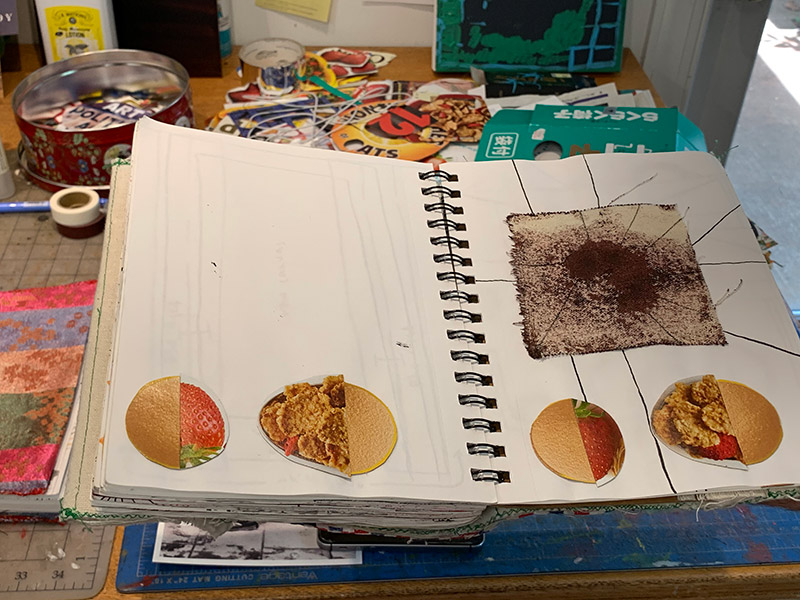

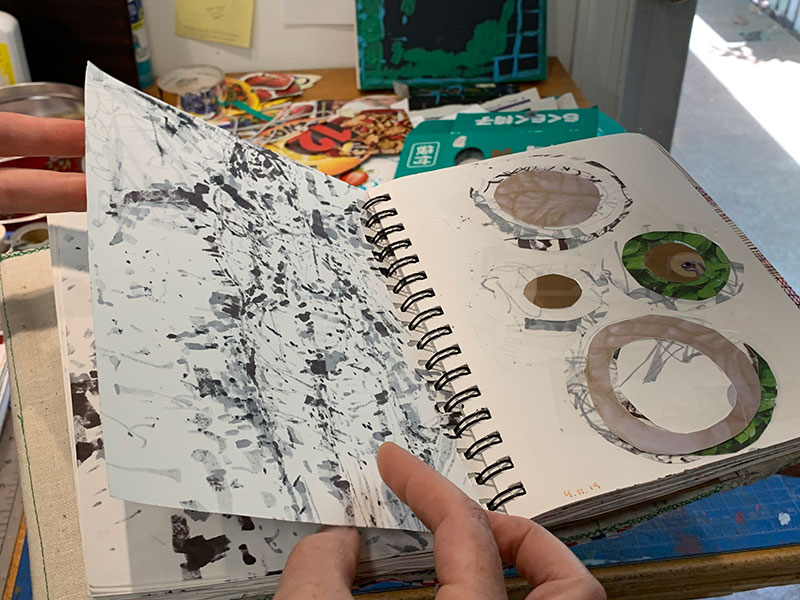

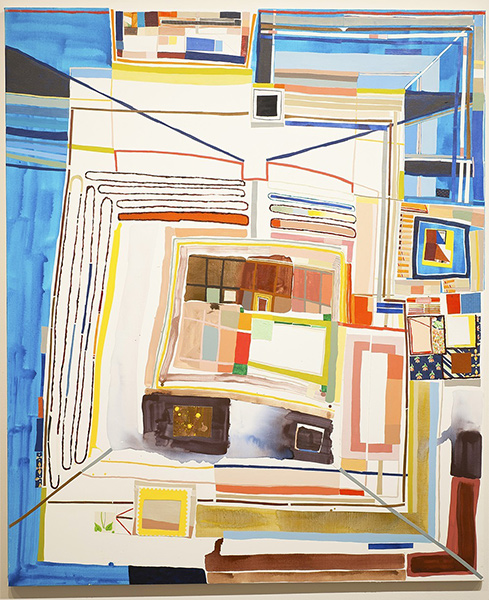

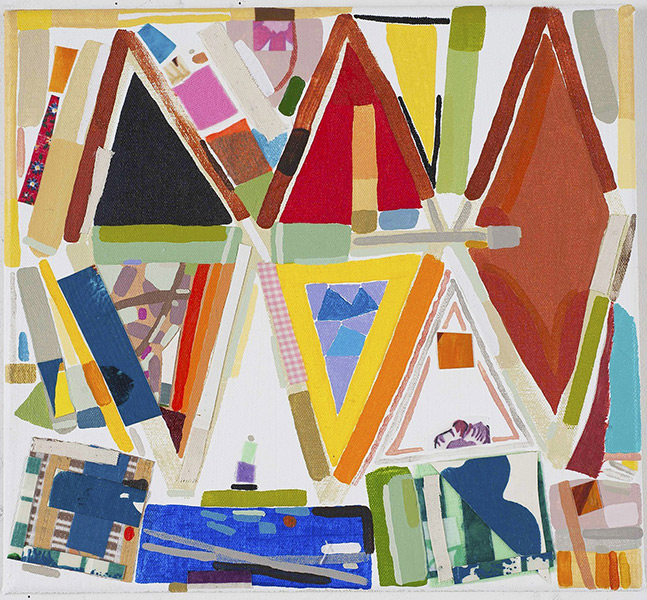

At first glance Campbell Thomas’ paintings present as some species of modernist influenced abstraction. Color, as line and block, orders a dynamic visual field, symmetry centripetally pulls edges toward centers, painted marks gather in clans –a cluster of X marks set off against a group of dashes. Often it feels as if the marks teeter on the brink of disorder but are then skillfully pulled back form the edge to evoke a God’s eye view, a planar perspective of a world below. Recognizable images glimpse through here and there, thus toying with a line between territories of abstraction and reference. Sizes vary considerably. Some paintings are as small as 9 x 9 inches others come in at 8 x 7 feet. The double take throughout is in the recognition that sometimes large portions, sometimes discreet sequences, of varied shape and size are in fact fabric that has been sewn into and collaged to become part of the actual ‘canvas.’ It is important to emphasize that it is very much the case that these inclusions are not experienced as elements placed upon the canvas surface but rather as becoming the surface itself, as if they were prosthetic extensions of the canvas. Whereafter canvas and appended fabric play a colonizing game with one another, a territorial struggle between sign and surface.

Thus line and color, as presence in the paintings are or can be the effect of a borrowed fabric. Once recognized, a sort of found object come ‘found color’ notion skitters across ones thinking about the painting’s surface. And sometimes one double checks, painted canvas or inserted fabric? Campbell Thomas describes the paintings as, for example in Equal Standing (2017), “Collaged fabric, collaged cut-up old paintings, acrylic paint on stretched and gessoed canvas.” The history of this set of formal choices furrows yet further into the lived experience of the artist outside the studio. As Campbell Thomas tells it,

“Several years ago, my mother journeyed south to my North Carolina home with a singular goal in mind.

She sat me down at the dining room table, threaded my unused sewing machine, and with the help of a

plastic bin of secondhand fabric scraps, she taught me how to make a quilt. At the end of the day,

I held up my first finished quilt—a mishmash of color and shape made from the odds and ends of leftovers.”

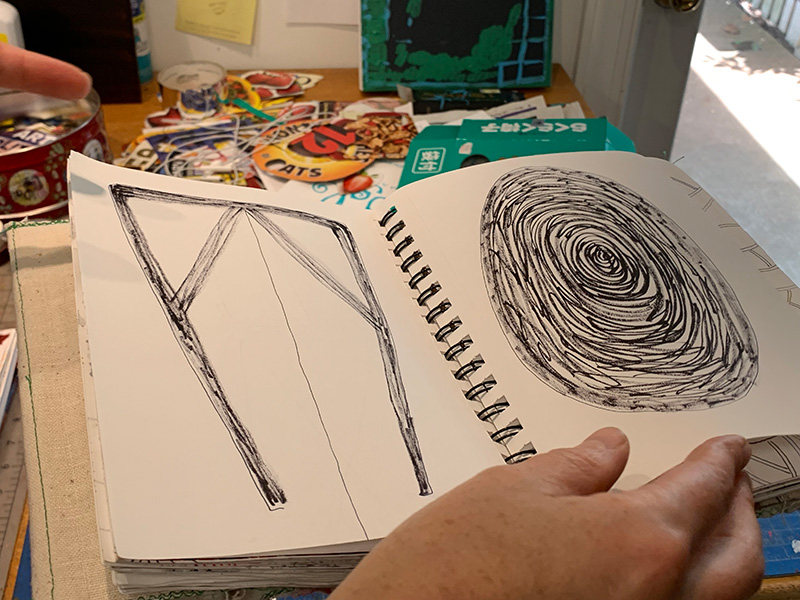

The sewing machine has since migrated from the dining room to the studio. And apparently there is no a circular migration. Campbell Thomas admits to having made one further quilt to refine her understanding of the process. Otherwise those skills have also migrated to the studio. In this way the know-how of domestic nurturing, anchored in an emphatically visual domestic culture, are passed down the generational line while ricocheting across cultural contexts.

Following the ricochet, quilting and gender, the history of quotidian, domestic visual cultures, even American regionalism (just think of the history of cotton and textile production in North Carolina), all become a piece of the dialogue shaping the work. As does the collision with Modernist iconography, because the devices of Modernism really are everywhere. Including in Campbell Thomas’s paintings.

Homages to –or more prosaic uses of– rectangles (of various dimensions) resound through Campbell Thomas and quilt making. Think of so many quilts where squares align with squares to complete the oblong object. For Campbell Thomas the division of visual real estate is more of a competitive struggle and less of a seemingly democratic allotment than it seems to have been for either collaborative quilt makers or for Josef Albers. [Or, come to that, for Anni Albers who blurred territorial lines between art and craft.] In recent paintings of Campbell Thomas, The Still Point (Line within Line), 2017, or The Still Point (2018) the squares and other rectangles, defined by sometimes painted marks and sometimes by sewn in fabric, jostle dynamically if not antagonistically. This jostling is a piece of the energetic quality the paintings offer. And, given the means by which Campbell Thomas constructs these objects, painted but also meticulously sewn in, (i.e. far from the brusque energy of much expressionistic painting), the striking sense of physical studio-energy is a commanding achievement. One feels the sense of the action of making the painting without it remotely mimicking action painting. In the paintings mentioned above the rectangle is torqued, gyroscopically, evoking a frayed sense of T. S. Eliot’s, “Still point of the turning world.”

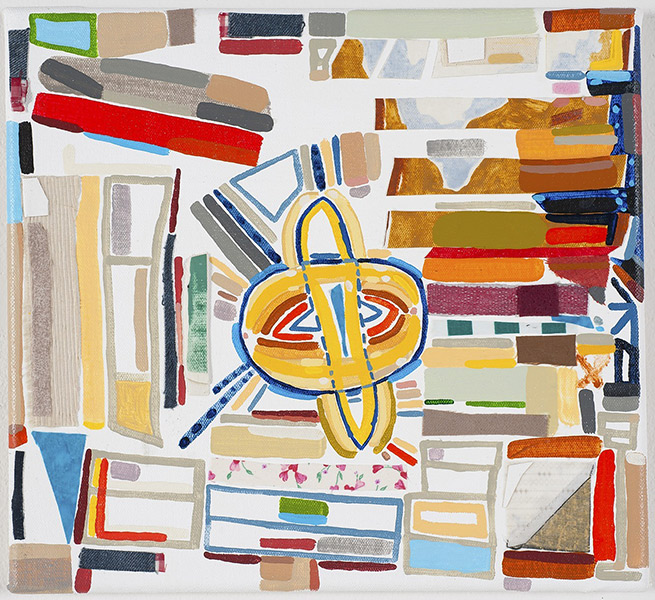

Some earlier work tacks east and west of the look and feel of quilts. Though, having said that, The Multiform (2016), could seem to pay homage to kin of a quilt, Rauschenberg’s Bed (1955). Which is to say both artists, in different ways, are interested in the notorious gap between art and life, between the hallowed and the quotidian. And, as if to emphasize that she treads in that gap, the artist, in The Detail of the Pattern is Movement (2015), gives us silhouettes of children’s feet, (Campbell Thomas’ children? aka her domestic life), dancing across the canvas from a brazenly rendered Halloween Jack O’lantern. While A Protean World (2015) reverses gears and clearly, blatantly evokes the visual logic of quilts, but sized at only 12 x 13 inches it confounds that bread crumb trail that the artist had seemed to offer. While in Lucid Geometrical Space #3 (2015),the cartoon ‘sputnik’ that holds the canvas’ center is a splendid glob of figuration struggling valiantly to signal as science fiction orbited by a sea of abstraction standing in for the heavens.

At times the balance between painted and found fabric reads as a sly dialogue. Choices of painted color, texture and mark are in a constant chatter with found versions of those same essential elements. In Accounting for Spin from 2013 found fabric and patterns hold the upper hand and the visual center of the painting simply by volume. Campbell Thomas’s task is in organizing them into a workable chaos that builds a subtle and seducing vortex that is also a seemingly impenetrable flat surface; the latter a centerpiece of late modernist conundrums. Found fabric patterns and textures speckle the visual field. Plays are set up between layers or depths of the painting’s surface, as if the canvas base were showing through in some threadbare manner. While brusque green stripes from found fabric are shaped into a pendant that points south, southeast. Unlike the more recent work –airier more open– here, the surface builds a density. It is impassable, impregnable, a wall is even evoked. But a dynamic wall, one moves around its flatness directed toward every compass point by shape, color and weave of fabric.

For Campbell Thomas this is a private conversation about two worlds. One, her daily practice in the studio; the other, an emblem of her other daily practice, i.e. home life. And inevitably –because she shows her work in galleries not spread out on beds at home– this all travels into the public sphere. No shortage of ink has been used to talk about the relationship between quilting and certain painting genres and the very different cultural territories they hold. Campbell Thomas is clearly aware that if she had lived 150 years ago, because she is a woman she would not have been a painter. But she would have made quilts. These are, then, emphatically paintings that without apology, but also without polemic, re-mix the vocabulary of quilting and the devices of modernism. They borrow from the artist’s own domestic scene, for example the aforementioned cluster of X marks in her paintings are loaners from her son’s to-do list, while the domestic embeddedness of quilting is self-evident. But her paintings also tilt at not so imaginary modernist windmills –the exclusion of women from art history being the most obvious. So while the work alludes to hard edge abstraction (and its taxonomic siblings) it also feels like a shrewd pastiche of that history, a rubbing of it against the grain. There is a squabble and a love song sung between the two cultural and personal registers.

In all this it does not seem that there is a strategy to undo hierarchies between craft and art. Campbell Thomas is a bricoleur, bypassing that struggle and moving toward a place where a hybrid spawn of the two will propel a series of questions about each. It will be like a series of meandering, thinking-journeys about each practice in front of each object.

More images can be seen at: https://barbaracampbellthomas.com/home.html

Exhibition on view October 1 -26 2019: https://www.thepaintingcenter.org/2019