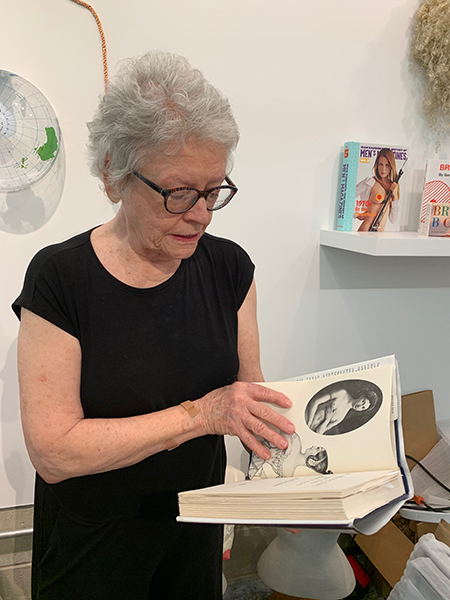

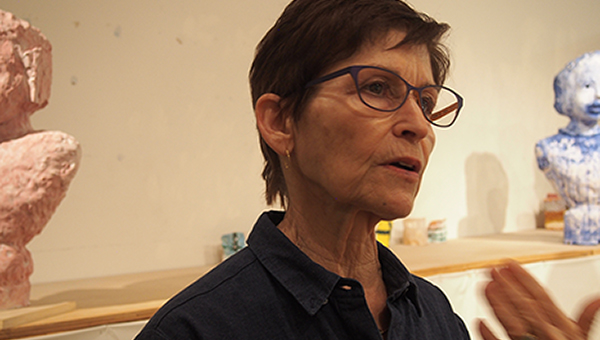

Carol Cole

In Carol Cole’s Studio

Carol Cole enthusiastically advertises that her thinking about culture has been influenced by the work of D. W. Winnicott. Winnicott himself was an enormously influential psychoanalyst yet, importantly, before that he was a pediatrician. It was this close contact with children and especially infants, and their present or not so present caregivers, that allowed him to speculate an elaborate fantasy of the infant’s inner life and its entanglement with the caregiver’s behavior. This speculation has become clinically essential to droves of psychoanalysts and psychotherapists. As just one such example, Winnicott posited that for the infant if the mother is absent the infant has no way of knowing if she is to return momentarily or if she is dead. Internally, and thus affectively and behaviorally, the infant —not to mention the adult— is destined to toggle between fantasies of the terror of loss and the gratification of sustenance.

Winnicott’s crypto-melodrama of deprivation and nourishment is often presented as a normative narrative of child development. It is a story of how the child experiences the objects of its world. And following the highly influential Melanie Klein, Winnicott came to see that the child’s relation to ‘part objects,’ that is, not fully constituted others but functional aspects of others, shapes this early experience. Such part-objects, in Klein’s thinking, tended toward the sexual or the genital. Foremost was a conception of the breast as nourishing, life giving, but also a breast as an either absent or present function. The Kleinian infant was either deprived or nourished and the trajectory forward, through a life of relational collisions, was shaped by this.

Cole, as an artist, as a collector and as a curator has had her thinking, in all those capacities, influenced by this Winnicott -Klein nexus. For Cole this is often deployed in an autobiographical, feminist practice that presents the Kleinian part object of the breast as synecdoche for nurture, and the containment of self –or, of course, harrowingly, the failure thereof.

Cole’s studio activity and her collecting, while not seamless, share a preoccupation with this urgent sense of need for nurture. And in all her endeavors it is clear that Cole sees nurture is not automatic, not a given. Nurture is often a matter of pushing through neglect, of persevering, of refusing to die.

F.E.A.R.S., Finally Everything as Remembered Simultaneously

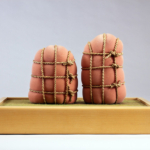

In her suite of sculpture and drawing titled F.E.A.R.S., an acronym she concocted for, Finally Everything as Remembered Simultaneously, (which just could be a description of the psychoanalytic process), she tours us through the catalogue of needs and catastrophes that might define a human subject’s reach for nurture. Titles like Martyr, Thorns, Fortress, Captive (all 1992) evoke the internal fantasies/experiences of the interpersonal staging of nurture and its failings. These are pieces, that as biomorphic forms, present clear and present injury and pain. Mirage (1992) a multi nippled sort-of-breast embodies the Winnicottian terror most aptly —too much breast for too many infants but nothing left over for me. Or, as Cole herself reports, in a conflation of nurture and destruction the fear was of being sucked on forever.

Work From Cole’s Studio

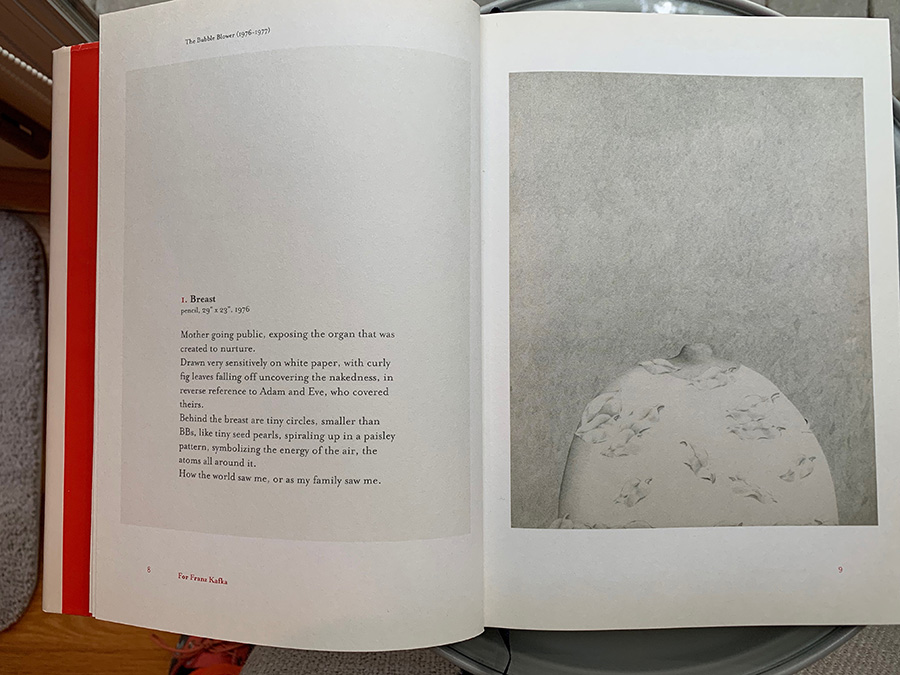

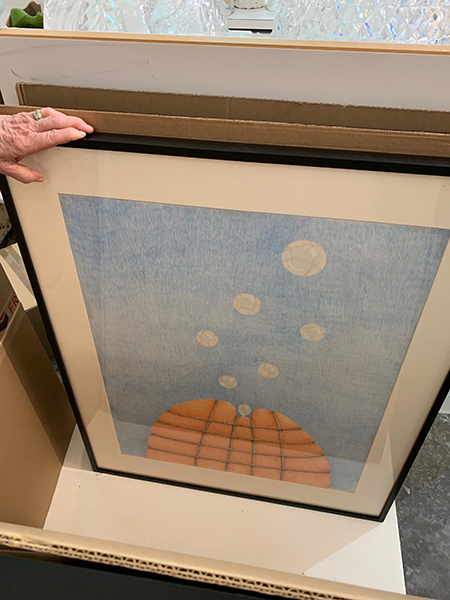

Cole signals her entry in the visual arts as occurring in the 1970s. Second wave feminist work, ideas and energy shaped her thinking in general while Judy Chicago’s specific injunction to “draw yourself as you see yourself, as the world sees you and as you would like to be seen” directed Cole toward a series of drawings collectively titled The Bubble Blower (1976). The principle, repeated iconographic element of this series of works is a breast with an inverted nipple. In a Klein-Winnicott universe such an image is a tireless rendering of nurture denied. This foundational body of work has returned and been revisited in The Resurrection of the Bubble Blower, a grouping of close to fifty sculptural representations of a single breast with a date range spanning more than a decade and a half.

From this latter group Introverted Nipple with Lures (1998) perhaps most literally resurrects the earlier work by inverting the nipple. It is also a perfectly imagined sadistic part-object, a breast surrogate with seductive sequins and satin, interspersed with fishing lures and their hooks.

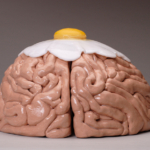

Surrealistic gambits, comedic dark humor and found objects rubbing shoulders with one another in jarring combinations are a hallmark of the body of work. This strategy can court absurd comedy, as in Brains and Egg (2005–2007) and sometimes what we might call a beguiling kitsch nurture as in Sweetheart (2000–2015) wherein, when the nipple is pressed, a concealed music box plays “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.”

It is also in this body of work that the dialogue between her studio practice and her collecting becomes most apparent. In this there is a mix of homage, conversation and kinship. Tuf, (for Nancy Grossman) (2004) spells out the relationship between Cole and the artists she collects most directly in that Cole also owns a Grossman leather bound head piece Y. W. (1969). Grossman’s allusions of sado-masochism, silencing and fear allude, in this context, to the complex routes that nurture, or neglect, needs to negotiate.

The problem, one could argue, with the experience of nurture, and its re-telling in the clinic, is the gap between intention and experience. Is the presented record of nurture, good enough (to echo Winnicott) or not and who’s to say. And in the case of psychoanalysis for how long, and in how many different ways, do you say it. Many couch-years later one may come to conclusions, or more likely a broader, deeper sense of experience. In a sense Cole’s studio process is that couch process. This can be brushed off as a lazy analogy to be sure, but Cole’s preoccupations as both collector and artist largely sustain it. After all, it is without doubt the case that our endeavors outside the clinic —perhaps especially in the studio— are too a working through of what we bring to the analyst’s office. Thus our broader, deeper sense of experience may emerge in the studio also. The problem here is perhaps most acute for psychoanalysis in that it makes more modest the notion of cure, while for studio practice it ramps up the ante. For Cole one might also think that the studio and the collection complexly engage in a conversation with one another. They allow for some of the different ways to say things about nurture. Thus Grossman’s S & M rhetoric of dress dilates the discourse about nurture at the breast for Cole in 2004, while Grossman could aver ignorance of the same rhetoric in 1969.

In Nancy Davidson’s Scrupulously Fake (1995), from Cole’s collection, the erotics of the breast (inherent to its nurturing function per Klein-Winnicott) return clearly unrepressed. Yet that de-repression is a complex on-off switch throughout Davidson’s work. For Davidson these breasts are, in their original form, in fact gigantic weather balloons dolled out in scaled up lingerie. The lure, the come on is there but the artifice and failure is written into the sculptural materials even if the erotic disappointment is offset by the humor. Thus as sculpture, the original form for Davidson’s work, the erotics and disappointments of nurture are evident form the get go. In the photographs including the one in Cole’s collection, not so. Scaling down through photography ushers the work several notches further into a realm of Camp erotica. And as Susan Sontag confirms in the very first paragraph of her Notes On Camp (1966), the essence of camp is its “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Davidson’s photographs play out the codes of erotica —but exaggeratedly and artificially. And, importantly, as her title lets us know from the start the eros is all used up, gone, “fake” but, complicatedly, it is still there.

Importantly Cole was born, raised and is resident in The South and there is present in her choices when collecting a sense of Southern culture. And in the literature —Southern, often Gothic— that Cole invokes as an important strain of influence in both studio and collection, complex desire and randomly dangerous behavior between people shape the scene. Cole touts Flannery O’Conner and Tennessee Williams as two shoulder angels. Given that alone, one could be forgiven for thinking that for Cole a veil of violence is a threshold through which Southernness —and nurture— must pass.

Take South Carolina born Charles Marsh. He was a peripatetic southerner living in New York, San Francisco and London and his work is infused with a sense of California assemblagists —i.e. he digested his travels. Still and all the assemblage piece of his in Cole’s collection, Klansman (1990), is a fully enclaved Southern narrative pertaining to the South’s history of racist violence. A smiling Klansman, hood atop head, Christian crucifix atop said hood, receives a gift (?) from an out of frame figure. The gift? An eye, an egg, a vagina? It is not clear, it is undecidable, but the aura of violence and harm is decisive.

Likewise with Louisiana born Gary Brotmeyer. His small collage, Mailer for the Philip Guston Show (1988), channels Philip Guston by intervening in a found portrait photograph. A vintage photograph, bordered in black like a mourning announcement card, Brotmeyer has succinctly masked the face with a cotton hood in the style of Guston’s Klansmen.

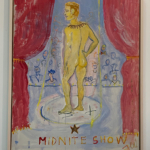

While Tennessee Williams’ modestly sized canvas (yes, he painted), “Midnight Show ND,” is very much about immodest display and complex desire. The scene is seen from behind a naked stage performer. The viewer of the painting stares at him from backstage, peering past his nakedness through the fourth wall confronting the voyeuristic gaze of the rendered audience. In turn, that audience is viewing his nakedness from the front. Gazes ricochet back and forth across the stage; a misé en abyme of complex desire unfolds. Nothing gets resolved, if there is anything to resolve that is. Instead desire is staged for all to see as a stalled imperative.

Into this intellectual context strides a Yankee hiding out in the south: Lee Lozano. Lozano is perhaps best known for her extraordinary conceptual pieces that perform, what was for her, a venture of self preservation come self rescue —indeed, self nurture— via the exclusion of others. Beginning in 1971, with a piece titled, Decide to Boycott Women, she decided to not speak to any other women —a decision she apparently stood by for the rest of her life— and in 1982 she chose to recuse herself entirely from the New York art world by removing herself to Dallas Texas where she remained for the balance of her life —She died in 1999. However, in the early 1960s, before the South became her refuge, she was also a painter whose work is rich with imagery of sexual violence and, indeed, what you could call complex desire. In the untitled 1962 Lozano painting that Cole owns the breasts of an upper torso, sans head, are rendered as two stars of David. The body is scarred, owned by a sign, a sign of identity that so recently, per the date of the painting, had been used as a passport to genocide.

Saint Louis based Adrienne Outlaw returns Cole to her own chosen iconography of nurture with Ma’am (2005). The piece, from Outlaw’s Fecund Constructions series, offers a breast shape protruding from the wall built from a range of materials –plastic, wax, collagen, feathers, cicada shells– and, crucially, a mirror. That last element, the mirror, is the indispensable key to the works rhetoric of self and other. As a viewer peers in –seduced might one say– to stare at the piece his or her own micro image is returned. The complexity of relational entanglements boomerang back and forth between viewer and viewed who, at least in part, turn out to be the same.

Returning north, with New Yorker Nancy Bowen, Cole has recently acquired for her collection Artemis Dilemma (2016). In Winnicottian terms the work is about a splendor of abundance, a display of breast-nurture for all maybe. But then again cantankerous psychoanalytical theory has its favored tropes and while the breast as part object is one of them. So too is the disordered body wherein upward and downward displacement of bodily functions and forms proliferate.

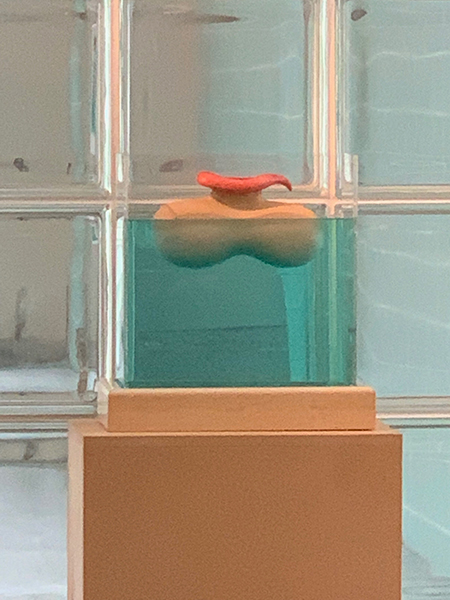

Perhaps the Bowen piece is well partnered with a piece from Cole’s F.E.A.R.S. series, Vessel from 2003. The latter, a biomorphic form adrift in a tank of seeming water, enfolds a biographical riff. Cole made Vessel as a form of memorial, a memorial precisely to a lost fear of swimming. Having overcome her anxiety, this alive seeming carcass, floats or drifts in a contained and constrained tank of water as stand in for the oceanic. But the piece also floats and drifts in a fully ambiguous territory between body parts from northern and southern bodily terrains; lips and breast and lungs and genitals abound. A hither and thither displacement of parts and functions that is conceptually and satisfyingly gathered together by critic Jo Anna Isaak , “The work celebrates of the lightness acquired in water, the surprising pleasure of the body’s buoyancy; large sensuous lips float above the water level like water wings, fat with suckling joy.”

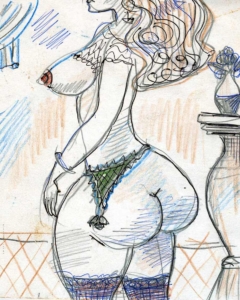

Cole’s collection also ranges wide culturally and geographically. Beginning in the 1950’s Miroslav Tichy fabricated his own cameras from cardboard and tape. Skulking around his home-town Kyjov, in then Czechoslovakia now Czech Republic, with ragged beard and shambolic dress, he sometimes surreptitiously sometimes brazenly shot images of women. A favorite haunt was the local swimming pool and he not infrequently drew the attention of cops. The photographs are frequently blurred, scratched and annotated with visual flourishes in pen or pencil. Some are printed crookedly and some have the sprockets visible in the print. In some sense they feel more like a riff on photography than photography. And though he studied at art school in the 1940’s, Communist rigidity per image culture seems to have taken the wind out of that sail. He remained a thoroughgoing ‘outsider’ until he and his photographs were anointed, in 2004, with a solo show curated by no less a figure than Harald Szeemann. It then turned out, discovered after his death in 2013, that he had all along also been producing drawings. Obsessively focusing upon the same erotic fixations but without need of a camera or real subject he was free to elaborate or exaggerate his erotic focus. Cole has one such untitled small drawing in her collection. Sort of in profile, but with a contrapposto torque revealing her buttocks, an extravagantly voluptuous woman, clad in lingerie with a red button nipple on the one visible breast, her head is then truncated just above the mouth by the paper’s edge.

Tichy visually commandeered the erotic potential of strangers and folded it into his fabricated world. This is not unlike the infant’s fantasy world, which Winnicott so carefully described, wherein the infant’s creative acts are gestures to overcome the disappointments to, or impingements upon its failed omnipotence. In Cole’s collection the piece broadens the range of how one might talk about nurture and its failings.

Isabelle Collin Dufresne, better known to most of us by her superstar name, Ultra Violet, was as well as one of Warhol’s original superstars, an artist in her own right. And though she participated in Warhol’s image circus the piece of hers that Cole owns elides the political puzzle around imaging women. In a move of mirrors without smoke Dufresne uproots the notion of woman’s to-be-looked-at–ness, so fetishistically and creepily upheld by Tichy, by transposing the representation into a sort of visual literature. In mirrored letters upon a mirror, contained by a fabulously kitschy frame, which more or less redirects the pleasure of looking to itself, Dufresne renders the word “AUTOPORTRAIT”. Which, it needs be said, is a real puzzle of a word. Not portrait by an other, not portrait of another but not quite self portrait. Maybe, optimistically, an “AUTOPORTRAIT” can be said to have some sense of dwelling in oneself, a sense of ones own bounded limits but without the gnawing, corrosive crisis of loss.

More of Cole’s work can be seen at: https://www.thebubbleblower.com/