Joyce Kozloff

QUESTION:

You have a long history as an artist and an activist. Did they start at the same time? Did your situation as a young artist provoke your activism? Did activism influence you work? Was there cross-pollination?

ANSWER:

Like many college students, I protested the American war in Vietnam and nuclear armaments in the 1960s. Alongside other feminist artists in Los Angeles and New York in the early 70s, I became an engaged activist, examining the assumptions and biases embedded within western, mainstream art and art history. Over the years, I’ve been on a pendulum swing between times of activism, and others when I pulled back into the privacy of my studio. There were periods during which my art directly reflected my politics, others when it became more recessive, but there has been a visible aesthetic continuum.

Once I understood that the prejudice against the decorative was based on a hierarchy that placed “high art” above the “minor” arts, which were associated with non-western cultures and female crafts, this became an exciting avenue to explore. By 1973, patterns based on architectural ornament and woven textiles were the primary source for my paintings, allowing my love of rich colors and surfaces to flourish. But there was still a gnawing feeling that I hadn’t really crossed over, so in 1978, I began working in ceramic tile and printed fabrics, and I didn’t paint on canvas again for 20 years.

Meanwhile, I was attending Pattern & Decoration gatherings with a group of women and men who were also questioning the aesthetic and gender biases within our culture. At the same time, I was one of the founders of the Heresies collective, which published a quarterly journal on feminism, art and politics. Those theme-based issues arose from exhilarating debates. I became a member of the editorial collective for the “Women’s Traditional Arts: the Politics of Aesthetics” issue. It was intended as an homage, but as we collected reports from anthropologists on the working conditions under which these magnificent objects were created, it became clear that their production could be a form of oppression (little girls going blind making lace for the courts of Europe). My appropriations from other cultures were another form of homage, which I have had to defend.

These issues were always present as I struggled to make art during those years. And then in 1979, I was awarded a commission to create a ceramic tile mural for the Harvard Square Subway Station (installed in 1985). It was an opportunity to reach a wider audience than the visitors to art museums and galleries: citizens who commute to work and pass through that space twice a day for their whole lives. I needed to communicate without pandering, so I began to dig for local sources, which would generate visual ideas. For more than 20 years, I produced 16 projects in transit stations, airports, schools, libraries and public gardens.

During that time, my private studio practice continued, but at a slower pace. There weren’t many mass feminist demonstrations in the 80s, and the progress we’d made in the previous decade was slipping away. Our numbers had diminished, so we invented guerrilla actions to disrupt the numbness and despair of the Reagan years.

Architectural projects begin with maps (blueprints, diagrams, elevations, floor plans), the scaffolding upon which I’d build my content. I soon realized that I could apply that methodology to more private work. By the early 90s, antique maps had become the impetus for most of my art. They are so variegated, peculiar, entertaining, beautiful, exasperating and enlightening! With their vignettes and cartouches, they reveal the history of colonialism, of conquest, of trade. Whoever names and maps has the power. I published a book called Boys’ Art, drawings that were a composite of maps of historic battles, my son’s boyhood drawings based on comic book wars of the superheroes, and excerpts from old masters and pop culture. It provided an opportunity to explore gender differences, as young girls don’t make these kinds of drawings.

By the turn of the century, I had burned out and extricated myself from public art. I was thinking about the horror of aerial warfare, as our media obscured its reality, rarely showing the victims. It seemed as though we were always bombing somewhere! At the American Academy in Rome during 1999-2000 with Italian woodworkers, I built a three meter diameter walk-in globe, Targets, which encircles the viewer with aerial maps of sites bombed by the US around the world between 1945 and 2000. Subsequently, I created several bodies of work employing European medieval world maps that represent geographies according to Christian orthodoxy; Renaissance charts of the world as seen by the explorers of other continents; tactical pilotage and nautical charts, with their military applications. During these years, I traveled whenever I could.

And then there was 9-11, the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, and a new global peace movement. We formed a group in New York called Artists Against the War, collectively organizing events and projects that utilized our skills to dramatize the invasion and its aftershocks. Our first action was “Drawn In” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on Moratorium Day, March 5, 2003. We invited members of the public to come to the museum and draw in the ancient Mesopotamian rooms, that very art that was in danger of destruction. By the end of the day, hundreds participated; the action was carried out simultaneously in 7 other cities in the US and abroad. Afterwards, we produced many powerful and outrageous projects and acts of civil disobedience in public places like the Hart Senate building in Washington DC, Grand Central Station, the military recruitment station in Times Square and the Republican National Convention in New York. It offered us a constructive way to express our rage, and I often brought our work to university campuses.

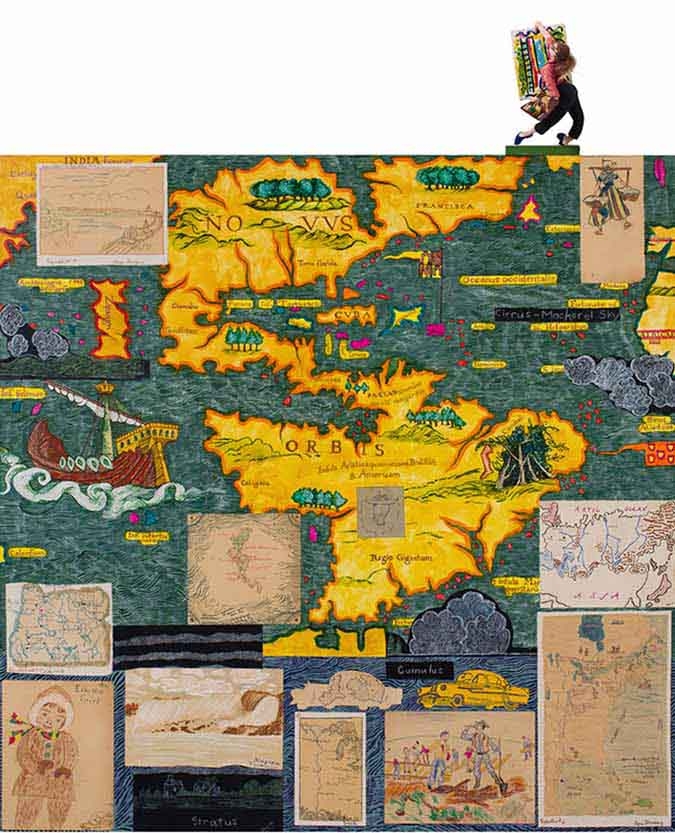

For the last six years, I’ve surprised myself by returning to earlier themes and concerns. The Islamic star patterns that had defined my pattern paintings became the structure for a new series, If I Were. I incorporated and embellished fragments of collage – excerpts from my long history of image making that were stored in flat files – into complex geometric webs. My parents both died in the last decade, and when we emptied their home, I found my childhood drawings. I had forgotten that between the ages of 9-11, I’d made a series of maps depicting states, countries and continents. I absorbed them into a new group of paintings based on early maps, which were as childish and “wrong” as my own. I’d come full circle.

While working on these pieces, Donald Trump was elected President. We quickly organized an artists’ resistance group, We Make America, which creates funny, colorful and smart props for political rallies and marches. And I’ve returned to the field of public art, which feels fresh, vital and right to me again. My project for the 86th Street and Central Park West subway station is up the block from my first apartment in New York, where I lived when I arrived in 1964. Creating it, I felt as if I were giving a gift to the city where I’ve lived for 55 years.

Although these are dark times, I try to maintain a hopeful dialogue with my community, believing that we must draw young people into creative activism. With the “Me Too” and Black Lives Matter movements, high school kids fighting for gun control, the youth climate movement here and abroad, immigrants rights groups resisting ICE and women revolting against draconian abortion laws, artists will become the visualizers of progressive ideas.

“An Interior Decorated,” installation Tibor de Nagy Gallery, 1979, variable dimensions: hand painted glazed ceramic tiles on plywood, silkscreened silk hangings, produced at the Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia, PA, the floor coll. Ludwig Museum, Aachen, DE

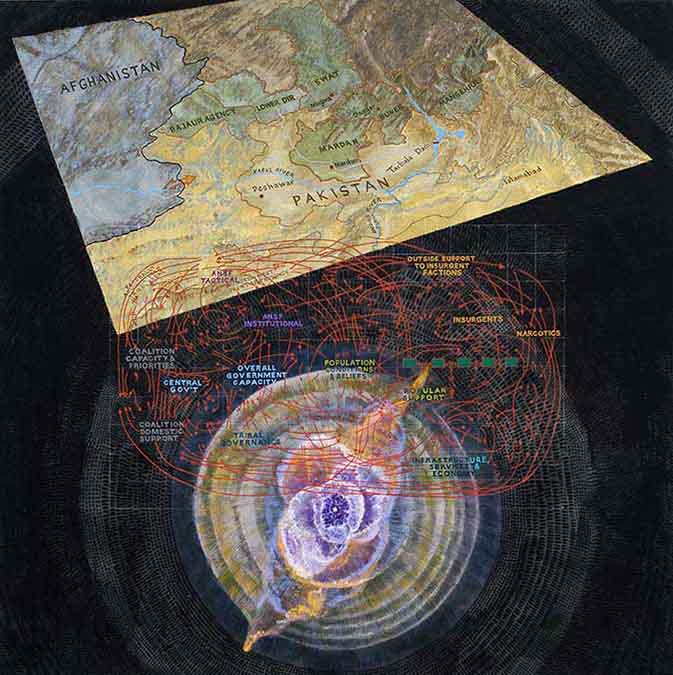

“The Middle East, 3 Views III: the Fight for Northern Pakistan” (right panel of triptych), 2010, 72″ x 72,” acrylic and collage on canvas

“Art Girl,” 2017, acrylic, collage and found object on canvas, 65″ x 54″ 6 1/2″, coll. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, PA

Beautifully expressed Joyce …so reasonable and thoughtful – through all these impassioned & hopeful battles.