Three Curators, One Office Visit

What does it mean to do an “office visit” with a team of curators? With artists, at least with pre-post-studio artists, still by and large there is a place of toil. Such artists will lay claim to a piece of geography, a piece of real estate with doors and floors, their studio. With a team of three curators that come together, dissolve and reform over the passage of the weeks and months there is not even an office, just a series of meetings had on the go, on the phone or online. Drop-box shares, Face time check-ins, texts and e-mails are the glue of the group, not real estate.

So, in no particular order: Annelie McGavin was born in England. She has traveled much and she has lived back and forth between the United States and England for many years. She has spent time living in Colorado and Texas, in the latter directing a gallery at the Dragon Street art hub. She has traveled to do graduate studies in England and she has returned to the US to live and work in New York City. In New York she has worked for Sperone Westwater and for Benrimon Contemporary and she has been gallery director at Studio 10 in Bushwick. She also curates shows at various other venues. A recent project on view in Allentown Pennsylvania at Cedar Crest College was a show, co-curated by McGavin with Rebecca Chipkin and Elizabeth Johnson. This show addressed the act of remembering, or, what you might call the very how of remembering, and, all but inevitably, the failing of that act.

Becky Chipkin is a native New Yorker –Queens. She grew up in a family of textile designers who helped shape her own visual culture. Chipkin and her identical twin sister Alex are itinerant printmakers. Limner artists, except with training. Together they can be found propelling their printing press, mounted on a bicycle, through New York streets on vagrant printmaking projects. They will turn up at sundry ‘art’ events and crank their press. It has the feel of an earlier street culture, something Atget would have photographed.

Elizabeth Johnson, also artist, also writer and curator has, like McGavin travelled much back and forth across the continent; California, Upstate New York, Philadelphia and rural Pennsylvania. Trawling through geography and its shifts, changes and cultural collisions has shaped her studio practice and curatorial acuity. In both her roles as artist and as curator, Johnson tacks toward “Fragmenting and mixing images” thereby separating “them temporarily from meaning”. The result is not a mere puttering bricolage, rather it is a recalibration of relationships between object and context. The various itinerant wanderings of all three curators will be an apt metaphor for the first show the group pulled off.

Collaboratively all three curators honed the idea for a show titled, Memory Palace. And, probably ironically, around this title they found artists who speak to the very faltering of the act of remembering. A memory palace is a metaphorical home for otherwise transient thoughts. It is a mental archive visualized and visited by the rememberer in an imagined, very purposeful walk through ones own mental landscape. A memory palace is also the anti-Proustian device. Proust remembered, tremblingly so, all but against his wishes because of a scrap of sponge cake. A memory palace, contrarily, is about wanting to remember. It is about avidly working to hold the thought, retain the image. The show, Memory Palace, gives us not exactly anti or failed mnemonic devices, but something like the debris of the remembering act and a sliding between Proust and the Palace gates.

Barb Smith forces sculptures into being from material that really does not want to remember quite that much. Using ‘Memory Foam’, the stuff of mattresses set to guarantee a good nights sleep (and all the contortions of dreamt memories that might offer) she casts the material at, so to speak, its very moment of remembering. Forcing the resultant twisted, form to remind us of modernist abstraction, but also to offer scene-of-the-crime like evidence of what just happened to the material at hand. This is memory foam that will never, ever forget. Smith tortures a micro incident of torqued polyurethane into a permanent signature of having been this way. If something never leaves the present moment it can never be forgotten, which just might be the same as being remembered.

Just as Smith’s sculpture invokes a modernist flicker of association so too Tiffany Calvert’s paintings turn upon so many traces of art historical marks channeled by the current artist. Such marks simultaneously altercate and collude with quotes or snippets from journalistic images and personal photographs. Passages of paint that we are told, or maybe recognize, as lifted from Goya, or El Greco shimmy and elbow around with more contemporary and personal references. It all has a lawless, Helter Skelter feel that skids animatedly toward a Rorschach effect. Having arrived there –at a Rorschach evocation– one can wonder what really does a projective test have you see? The test’s mechanism is to point toward the mode of Proustian involuntary memory. Or, putting it more psychoanalytically, the test is pointing toward the palace of forgetting, repression. Calvert’s paintings are, then, also about that palace. Forgetting and remembering joust across the paintings as marks that are held in semi permanent tension between remembering their original context and negotiating their new one. This is a dynamic experience of decision making for the viewer as much as, one imagines, for the artist. Gestures, devices and quoted passages of paint deliberately do not quite link up with other marks to produce a consensus. It is as if the marks do not remember where they belong; or they remember all too well where they belong, and this is not it. Calvert, then, assembles a squabbling quorum of marks that reach no consensus but are avidly working through the relationship of quotation, originality and memory.

The third artist in the show, Jarrod Beck, convenes, as his work, materials that might be used to invoke, anything ranging from say, historical memory to agricultural cycles to geological eras. Time, the life-world of memory, is hugely present in his work. This can lead him as far afield as urban history in Birmingham Alabama or to the topographical memory of the shifting, over months and years, of eroding soil along a messa in west Texas. In Memory Palace Beck hangs wall pieces that robustly invoke one enemy of remembering, decay. The work at first appears as rotting layers of wallpaper, fabric (or even the torrid wall-posters from The Cultural Revolution; the latter usefully erasing memories of yesterday’s truth for today’s version of the same). Yet the true paradigm for Beck’s wall pieces is much earlier than 1968. It is the palimpsest of erased, but not quite so, messages that insistently assert their presence in and through the new message. History actively refusing to be forgotten might not be the same as history being remembered: it perhaps comes down to a question of agency. Beck is the agent here finessing areas of local incident within each piece while teasing the presence of half forgotten voices back and forth. The pieces in memory palace, though large, are smaller than much of Beck’s prior work. Scale and time seem to have a metrical and syncopated relationship for him. Indeed one of Beck’s pieces in Memory Palace, Together (2015), is actually made from prior work. Recycled, remembered we might say, from a much larger installation in Provincetown Massachusetts last year, Together remembers the artist’s own work as, in curator Elizabeth Johnson’s words, “an epic destructive backstory, one that was forgotten, edited out or lost over eons”. Here it is re-remembered, called into place as an evocation of decay that paradoxically restores itself.

In an upcoming project with the same team of co-curators slated for another –thus far unnamed- university gallery in Pennsylvania, we will witness winter itself poured into the gallery space. Space is the Coldest Winter will bring the frigid light effects, atmospheric effects and the affective mien of winter to the cloistered space of a university art gallery.

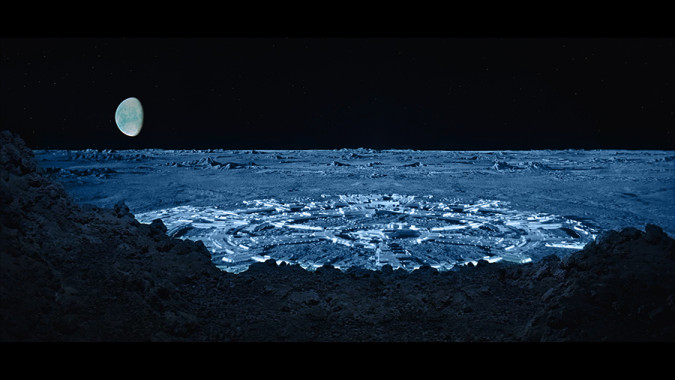

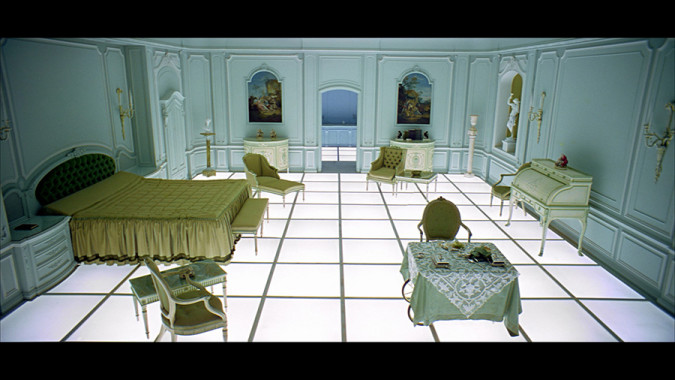

Setting the scene, with the past of the future, artist Josh Azarrella will screen his version of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey. In 1968, the year of the original film’s release, political-cultural anxieties about the aforementioned Cultural Revolution shared space with political-science anxieties about a nuclear winter. Potential bomb-lobbing superpowers provoked a cultural turn toward ambivalent utopian/dystopian fantasies. Kubrick’s two outings in this proto-genre were Dr Strangleove (1964) and 2001 A Space Odyssey (1968). Azarrella, Making common cause with HAL, the computer of Kubrick’s latter film, manages to digitally banish all the characters from the space ship Discovery One. In the original film HAL the over protective and probably psychotic computer was trying to protect humans from human error. His solution was to eliminate the humans from the ship. Alas, or not, he ends up lobotomized and singing “Daisy, Daisy give me your answer do,” as the last human on the ship, Dave, disassembles his electronic brain. What HAL was only partially able to do Azarrella has completed. Adrift in space an empty ship will perhaps find that spring, and the original film’s birth of the Ubermensch, Star Child, on the far side of the Jupiter horizon, is deferred. How bleak, then, is this winter to be? Azarrella’s digital manipulation has a neutron bomb effect. And the Star-child birth must presumably be restaged as a nihilistic winter of HAL and Daisy’s spawn. Ecce homo comes slouching toward Bethlehem Pennsylvania.

Concurrently Stephen Truax will present atmospheric, large-format photographs that edge toward a different mode of bleak emptiness; to wit the seeming collapse of photographic verisimilitude. There is little in these photographs that is recognizable or namable for the viewer. The images are created by, variously, photographing, multiple-exposing, scanning and then digitally color correcting. The images espouse diverse referents that finally are ungraspable. Yet simultaneously they tease. It is as if they gave us indexical signs of winter itself playing upon the photographic emulsion and chemistry. Thus standard formal devices of photography have an attenuated presence and pose as the signs of a somewhat painterly abstraction. There is a drifting, somewhat Turneresque quality to the layers and areas of color. Indeed for a show that is set to play upon climatic drift and atmospherics these images harness perfectly photography’s often unsung and uncanny ability to show and tell very little but evoke an enormity. Just think of Niépce and the first photograph. Not so much its historical freight (as the first photograph) but how little of what was to come was available. It did not show a place so much as evoke an affect. The drifting, hazed quality disorients, un-orients the viewer. The camera, perspective and its constitutive effect are, if not voided, forgotten. In the space of the coldest winter there will be no locus. No place from which to sustain a point of view. Truax’s deliberately, formally barren photographs nudge the viewer toward a pastel hued white-out of not knowing which way is up or out.

We could think of the curators as having finally decided to bring places to meet an audience, meet people, rather the usual way around where people, an audience come to a place. The place in this instance is multiple. It is inevitably, a place where art confers with its old friend and enemy the white cube. But there are also specific if elusive places. There is the place of cinema past and how that place was experienced as it rendered the space and time of the future. There is the space between the viewer and the photographic sign. And there is what happens to that space when the sign doesn’t do what it is supposed to do. When photographic transparency is blurred and the image thus blinds us. And then there is the space of space. Lurking constantly in the wings of Space is the Coldest Winter is outer space, the deep space of science fiction but also of inter-galactic fact. It is a space that offers very little to sustain human life. It is this space that shades the whole enterprise of Space is the Coldest Winter.

Both Robert Hickman and Esther Ruiz are sculptors whose work speaks to how we might experience or negotiate this vast space of a NASA explored perma-winter. Esther Ruiz’s chunky concrete sculptures come at one as if from an ethnographic foray beyond Jupiter’s horizon (Where we might presume HAL and Daisy to still be). Small, hugging close to the ground, some signal to you in neon others, less demonstrative, brandish plexi-glass or natural crystals. Light, reflections, glimmerings, all will project the work’s presence beyond its immediate location within the show. Beacons in the perpetual winter of deep space, they are slyly anthropomorphic, or perhaps better, robo-morphic, Yet because these sculptures also suggest robo-debris they refuse to deploy the sign of the cute that has plagued so much of science fiction since the Star Wars franchise. Instead their very stolid immobility charts space for others, perhaps the viewer, to navigate their way through winter.

Theatrically the task of pulling off the illusion of deep space might fall to Hickman, an artist who frequently works with glass, manipulated in all possible ways both materially and metaphorically. (For example imagine a disco ball for Buckminster Fuller). Hickman’s sculpture will, here, not be earthbound. Instead, installed as hanging pieces, available to be experienced in the round, the sculptures will appear to hover or drift. For Space is the Coldest Winter, Hickman will install two large – 2 and 3 feet diameter– disc-come saucer shapes fabricated from hand-cut pieces of glass. One sculpture will be gold leafed, the other silver. Facet by facet one can imagine the refractions of light, perhaps like Fuller’s disco ball, scattered across the season. Such refractions and dispersions will have the power to undo, to dematerialize objects and space. They will intersect with, even interrupt, the work of the other artists in the show and they will dematerialize the space itself.

Much undone, as it has been, over the course of its life the white cube will here, via Hickman’s refracting sculptures, resiliently return the cruelest months for our experience. Mediated by a cohort that includes Chipkin, Johnson and McGavin but also NASA, Space is the Coldest Winter speaks to both the anxious drive for interstellar scrutiny and also the conventional architecture of display and exhibition. After all, how exactly does one show and experience an unvisited and unknown environment? Mentored by geography and its climate the curators have seized upon a space-climate continuum as the site for a reverie upon unavailable knowledge and human absence. Partly the show is the result of McGavin, Chipkin and Johnson thinking about the lived experience of winter. Winter in New York City (or Allentown PA, or Colorado), where it is dark at 4:30 pm, a time where the space we live in and through pushes hard against us. A time-space that seems unwilling to support human life: it shuns our presence.

No curator ever actually ventriloquizes the thoughts and desires of the chosen artists. (Nor artist the thoughts and desires of the curator). They instead collude to collate, juxtapose, pose in not so neutral corners to allow the setting up of novel discursive parameters with each reshuffling of the deck.