No crime scene here – studio visit with John Monti

Probably it is an effect of wallpaper in general? Perhaps all wallpaper offers the same all over, plenary sensation. Probably it is an effect of a whole room, floor to ceiling, awash in a relentlessly repeated pattern; no beginning, middle, end or visual exit. Strangely at the William Morris museum in London one does not get that sensation. Wallpaper, floral wallpaper, being Morris’ stock in trade, one might expect it to be so throughout the building which had also been his home. Instead the museum has taken his wallpaper designs and selected, framed and displayed them in cases upon the wall. Shot out a slight distance from the wall they should nominally be affixed to, the designs and floral images are thus foregrounded. Pushed from the to-be-barely-noticed walls, into our faces the floral designs are domesticated by being divorced from their intended domestic application. The overabundance of ornament has been contained, corralled.

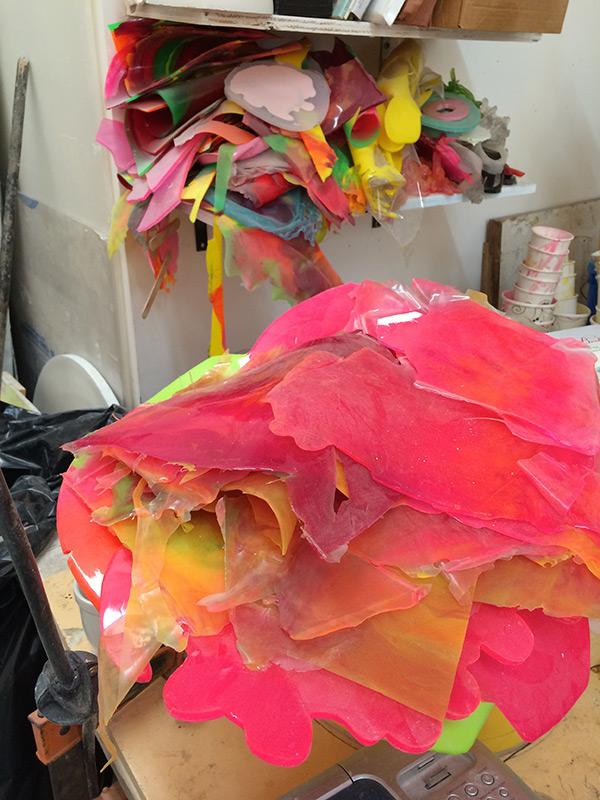

In John Monti’s Brooklyn studio no such wrangling has occurred. Coils and tangles of cast plastic flowers push toward and leer at the visitor weaving their way between worktables and display stands. Tripping or being garroted by a sculpture seems very possible. Physical and emotional struggle is in the air. Combat is probably not far away.

Monti’s work currently has two principal registers. There are the floral concoctions that can vary in size from as small as a tabletop piece up to a much larger space invading taller than human scale. And there are flat wall mounted pieces made from mirrors that become almost entirely opaque following the application of many layers of pigmented urethane rubber. The mirrors and the floral sculptures array like a complexly blocked ensemble cast obscuring then revealing each other, each democratically taking its turn as the visitor walks through the studio. In the floral sculptures Monti concocts an image out a slender reference while with the mirror pieces, image is all but entirely banished. There is abundant color in both sets of work. Bright, sometimes iridescent colors and metal-flake finishes from the world of custom cars and hot rods glare at the visitor. Artifice abounds.

The flowers, and their tangled underbrush inevitably dominate the space of the studio. Their placement choreographs the visitor’s route through the space. And there is a powerful sense that, at least metaphorically, one could get lost in the shrubbery. As flowers go Monti’s tend to not invoke exotic flora. Hoi polloi flowers with a basic system of petals and stems, some opened up fully to the sun, some caught in the precise moment of about-to-open, like one of those time lapse nature films. In a sense they are cartoons of flowers. Invented by Monti to signal ‘flower,’ rather than to mimic recognition of a specific genus. They present us with unruly nature as a sign of, well, unruly nature. But this is also unruly nature frozen in time and space by the artifices of custom-car culture, and the lavish over productions of rococo excess.

Monti works alone in the studio, without an assistant. (Though his dog is often there). The practice is very much his own personal domain. The day spent in the studio is all about his obsessions, curiosities and fetishes. The walls are peppered with cut out shapes and reference images. There are French curves and oversized flower shapes; stamen, petals and pistils. Images of past work –say the costume Monti made for dancer Jodi Melnick, or the large piece he installed at Greenwood Gardens in Shorthils NJ – are crowded upon and surrounded by references for new ideas. This accumulation smears across the background of his workspace terminating at his archive, the collection of pieces, parts and starts that never got any further but must needs be saved. Indeed this archive marks the boundary between the workspace and the storage area.

While working Monti will often have the radio playing in the background. And though its current offering may or may not directly inform the work the feel of the place is that some riff upon elements of popular culture creeps into the studio. The only actual pop culture reference recognizable in the studio is an image of Little Peggy March high up on the back wall where she is slightly overshadowed by cardboard templates of petals.

Monti’s craft practice has its conventions and traditions around which he, like any artist, innovates upon in his daily toil in the studio. The feel is a mix of craftsman alone in his redoubt and under-capitalized small factory operation. Monti casts for example each flower piece, or segment, multiple times over. That is to say he will generate a large number of identical pieces that will, as they are used and recombined, lose their factory identical-ness as they are deployed in larger agglomerations of flowers. Thus atop and beneath his main worktable are boxes of identical flower pieces –like the days accumulation of a piece worker– awaiting their assignment in the larger scheme. To see these pieces in differing stages of completion, from rough cast element just removed from the mold up through refined and finished object is to visually unpack the process that is masked by the sheen of the finished sculptures. The flashing, the seams, the joints, all are visible. They are barefaced and undecorated. Which is to say the ornament to be is very plain and undisguised.

In The Grammar of Ornament, Owen Jones, insists that ornament, or decoration as he would often have it, is used, indeed needed, to conceal the seams between the constructed and functional pieces of the designed world. He is thinking of architecture mostly wherein decoration masks the rougher edges of, say, two planes meeting. But he extends his thesis to all areas of decoration in the arts. For Jones this decoration has, then, a function; concealment of the imperfections of architectural craft. But for Jones decoration also has an emotional destination. That destination is “repose”. “Repose” is the desired result of ornament, its terminus. And repose, he is quite clear, is what “the mind feels when the eye, the intellect and the affections, are satisfied from the absence of want”. Read politically want is held in abeyance and ornament stalls conflict at the decorated gate. It seems, thus, that it is also the case that decoration pastes over the cracks in the cultural world of, for Owen’s time and place, the ascendant bourgeoisie. Ornament masks want or emptiness. Ornament is the stand in for cultural content or political power.

One thing that we can clearly say about Monti’s ornaments is that they ornament absolutely nothing. In Monti’s work the concealing and pasting over devices of Owen’s logic are thrust into the foreground. Function is abandoned. It is as if there were no underlying algorithm, merely a blinking screen icon causing nothing to happen. Yet in its way Monti’s sculpture is too about an absence of want. Everything, but absolutely everything, seems to be there. However it is less about political want and more about the trained want come greed of spectacular culture. That which, per Owen, should promote repose in fact, per Monti and the life-world he inhabits, prods and jabs viewers into excitation with metal-flake finishes and iridescent candy colors. Repeated, replayed, redoubled the work is the exuberance of bling or kitsch loudly screaming out.

Yet Monti’s screaming voice is not necessarily in agreement with the discourse of spectacular culture. Monti detours ornament. By amplifying ornament, by alliterating it he points it back to itself, makes it address itself rather than an anonymous subject of spectacular culture. Ornament becomes an active mode of address rather than a nascent term within a “grammar’. Here we are identifying a device of Monti’s, which we may collate under various labels: alliteration, accumulation, amplification or agglomeration, each seems appropriate. Whichever we choose it is this which takes us to the affective heart of his studio practice.

The repetition compulsion was, at its least romanticized, Freud’s keyword for the struggle to master or to bind the unwinding emotional terror of trauma. Within the ritual of the repetition compulsion the trauma itself is never named it is only reenacted. The trauma itself inevitably –always, without fail‑ circled around some traumatic loss. At root it would be the narcissistic loss of plenary unity; that is the discovery of the other and the concomitant discovery of the abandoned self.

The signal moment from Monti’s body of work per this impossible mourning is his sculpture of a smile. This smile is a somewhat older piece of sculpture that Monti had not even planed to show us during the studio visit. Coaxed into unpacking it Monti’s smile turns out to be a bright, shockingly pink upside down pair of arch shaped lips. This particular smile is one of a group that ranged in size from the one pictured below, up to as big as the four foot one we saw hanging on the studio wall discretely half obscured by plastic sheeting.

There might be a punning play available here, something about the smile being the face’s ornament. And this pun may be of some use to us, may be worth saving. But more importantly we should hold onto the notion that the smile signals a relational event. Even when it is an inward gesture, a joke with oneself that draws a smile, say. Thus a smile is a form of address, from one to another. Of course with Monti’s smile there is one fabulous precedent to not be ignored. Monti smilingly re stages, as Lewis Carrol did before him, the traumatic loss and dissolution of corporeality. Off with his head cried the Queen of Hearts per the Cheshire Cat who had beaten the Queen to the punch. John Monti’s sculpture is similarly the smile of the disappearing Cheshire body. And, better yet, turn away ones eyes from Monti’s Cheshire grin and hanging on the studio walls are those mirrors ready made for sitting shiva. Monti’s imageless mirrors reflect a social space of denigrated subjectivity and absence of bodies, faces and smiles.

Almost entirely opaque the mirrors allow the tiniest glimpses of reflection. So tiny that they allow you to see no more than that these are non-functioning mirrors. Vastly, horrifically attractive with their super abundant slick of exciting color and pattern the mirrors offer a substitute back to the viewer. Rather than reflecting an image of self the mirrors offer ornament; strangely austere and function destroying ornament. Too much ornament and what is ornamented disappears. How strange, “A grin without a cat” said Alice; an ornament without a concealed function refrains Monti.

There is also a beautifully resonant classical precedent for Monti’s floral arrangements. For the Cheshire cat, the grin without a cat is protection. How can you chop off my head if I don’t have a body to chop it from? For Daphne, in her different way, ornament is too protection. Daphne, beautiful daughter of the river god Peneus, is lustfully chased by none other than Apollo, in desperation to avoid Apollo’s advances she calls out to her father to help her. The river god magically transforms Daphne by merging her into the surrounding foliage of the riverbank. Daphne is shape-shifted to transform herself into the forest itself and to become thusly a laurel tree. Which is of course nothing less than the tree whose swags of leaves are used to garland heroes and winners; or, if you prefer, to ornament heroes and winners. Ornament is disguise or camouflage but it is also armor. So, to guard against abuse, or love, or trauma, or any combination of the above, one resorts to decoration.

Love is Enough was a William Morris’ metrical romance of 1872. Metrical romance being a literary genre wherein poetry slaughters prose (of course) and where the ending is, inevitably, a happy reconciliation of lovers: Eden not so much regained as improved upon. Morris’ design for the initial capital letter L of his title delivered to the reader the letter L ornamentally entwined with, or perhaps embraced by, Laurel leaves. Love restores or repairs the initial traumatic loss or so the story goes; and not just in metrical romances but in psychoanalytical stories too. For Morris love is the major cultural trope of loss, rescue and social deliverance. William Morris is important to John Monti. Morris is someone Monti has looked to both for the beauty found in the tapestries and floral designs, but also for the socialist agenda of Morris’ practice. In Monti’s words Morris “had a social agenda, that of the enhancement of everyday life”, it is an agenda where the decorative becomes a “type of propaganda”. A propaganda of socialist love could we say?

Famously Adolf Loos dubbed ornament a crime when committed in the Modernist universe. Monti dodges jail time by reaching back past Loos to reveal ornament as a device of familiarity than can nonetheless estrange our knowledge about how it is to be used.

Monti’s Flower Cluster Grandé (2015), above, is included in The Crayon Miscellany

at OMI Fields Sculpture Park opening June 13

Provocative and exciting- both the work and the review!

Thank you!