Notes on dOCUMENTA (13)

The orientation of dOCUMENTA (13) is global, it reaches new centers of interest such as Afghanistan, Canada and the Middle East and it includes many emerging artists who are absent on top-100 career lists. Not only artists but also scientists and scholars have contributed to this Documenta – “from activist to zoologist” as artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev has stated [Artforum]1. Thus she speaks of ‘participants’ rather than of artists. A holistic vision is one of the reference points that Christov-Bakargiev has put forward for looking at the works. Another reference point, one that intrigues me in particular, is the notion of ‘the worldly’: of being aware of the world. In Christov-Bakargiev’s view human beings have this awareness but also the stone, the dog, plant, or meteorite. Being ‘worldly’ implies having knowledge, including “the knowledge that a plant is using when it turns toward the sun” [Artforum]. Another reference point, connected with the theme of knowledge, is that of the ‘riddle’. It accentuates the enigmatic character of forms of knowledge which we as human beings do not possess. With Christov-Bakargiev’s notions of ‘the worldly’ and ‘riddle’ as my reference points I wrote these notes. This is not a review of dOCUMENTA (13) but an account of how the works of a few of the participating artists shaped my thoughts. As I base myself on the notes I took during my two-day visit I decided to write it in the present tense.

In connection to Ryan Gander’s work I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorise (The Invisible Pull) (2012) which has one of the most prominent places in this Documenta, the Guidebook speaks of his “rhizomatic system of perception” [GB p.66]. In my view Gander’s perception mirrors that of Christov-Bakargiev, and provides a useful mindset for visiting documenta (13).

In my notebook I wrote a list: Ryan Gander> Lawrence Weiner> Korbinian Aignier > Anton Zeilinger > Georgio Morandi > Mark Lombardi > Hanna Ryggen > Vandy Rattana > Kader Attia > Margaret Preston > Emily Carr > Gordon Bennett > Michael Rakowitz > Song Dong > (and a wild card:) Nordic singing. I see my list as a pattern of roots and branches. Rather than going from best loved to least loved work I followed my intuition and I will see what sense I make of the pattern.

Korbinian Aignier (1885-1966) has a huge room committed to his work. The walls are lined with postcard size drawings (gouache and color pencil) of the apple and pear breeds he cultivated – Aignier was a priest, artist and cultivator of fruit. There are generally two apples or pears per card and sometimes a single one; each card is numbered in the top right corner. The emotion expressed in each small drawing is not diluted by the sheer quantity of the drawings in total but is, on the contrary, intensified by it. It is amazing how a simple narrative of two apples leaning against one another, standing alone or separated by a slight space in between seems to express a complete life. Giorgio Morandi achieves something similar with his bottles and boxes, which are on display in the Rotunda section along with his paintings. I see a lineage from Aignier to Morandi and forward in time to (neo-) conceptual artists such as Mark Lombardi or Roman Ondak, who are fascinated by archiving and cataloguing but whose works have a different ‘signature’. Aignier’s austere concept paradoxically generates very sensuous images.

Korbinian Aignier

Korbinian Aignier and Mark Lombardi

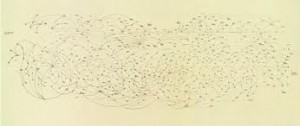

This is one way to look at Aignier’s work. Another one is to take into account the way his work is presented: in the same room with Mark Lombardi’s drawings and adjacent to quantum physicist/participant Anton Zeilinger’s room. Zeilinger has adapted laboratory experiments so that his assistants can demonstrate them within the situation of dOCUMENTA (13). I am no judge of quantum information technology and do not dispute the Guidebook’s claim that “his findings point to a renewal of the discussion of the definition of reality” [GB p.134]. Lombardi (1951-2000) traces in his drawings (secret) connections between financial institutions worldwide and international terrorism. There are three large drawings together with a collection of index cards on which he noted his research. It is explosive stuff; Lombardi’s drawings were under scrutiny from the FBI, who was particularly interested in them after ‘9-11’.

Anton Zeilinger

Seeing Aignier, Lombardi and Zeilinger together, I wonder what they tell me about ‘being aware of the world’. As I perceive the works with my senses I notice how different their ‘hardware’ is: the scientific instruments of Zeilinger, Lombardi’s large sheets of soft paper and Aigner’s small rectangled cards. From perceiving these actual works I make a leap to my memory of Ryan Gander’s breeze I Need Some Meaning I Can Memorise (The Invisible Pull) and to my memory of Ceal Floyer’s voice, both in the Fridericianum. Then on to the 37 ton meteor which in the end could not be transported to Kassel from Argentina and I imagine how heavy it would lie in front of the Fridericianum. Each work is ‘aware of the world’ in its own distinctive way with its own “shape[…] and practice[…] of knowing” [BB p.4]. I give a few more examples.

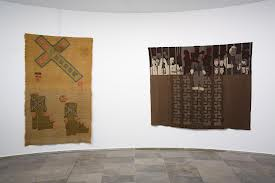

Hanna Ryggen, The Hitler Carpet (left) Hanna Ryggen, The Hitler Carpet (detail)

Firstly, the work of Hanna Ryggen (1894-1970), which is placed around the corner from Aignier, Lombardi and Zeilinger. Ryggen’s tapestries bear titles such as The Hitler Carpet; Gru. From the Civil War in Spain or Etiopia (made in protest to Mussolini’s invasion in Ethiopia). As the titles indicate, their subject matter is highly political – Ryggen herself was active in the Norwegian Communist Party. The weaving technique on the one hand accentuates the labour aspect of the work: I think of the loom not the painter’s brushstroke. On the other hand, it opens up ‘soft’ connotations of feminine craftsmanship and fairy-tale spinning wheels. When I stood in front of the tapestries this latter aspect came to my mind first. The tapestries took me by surprise, I had no previous knowledge of Ryggen’s work and noticed the weaving technique before focusing on the iconography. Thus, a chopped-off head on The Hitler Carpet struck me first as another colored patch in the weaving pattern, all the more so because I had looked at it from up close. Stepping back I realized what was being depicted. I took another look, slowly, at pace with the slow and painstaking weaving technique. I saw the colored threads, which transformed into the chopped off head in mid-air, I noticed more figures, then the title The Hitler Carpet and lastly the date: 1936. Reading the work at this pace felt like witnessing an explosion in slow motion. There is a short circuit in Ryggen’s work between violent imagery and ‘soft’ associations to which I can add my association with Nordic singing, on long winter evenings.

From Ryggen’s tapestries I went back to Mark Lombardi’s drawings. The elegant curves connecting big and small circles have a feel of embroidery, of buttons hand-sewn on a pillow, more so than of factual diagrams. The short circuit here is between explosive political content and formal aspects of the drawings. The drawings’ aesthetics is in total contrast to the ugliness of their content. And, like with Ryggen’s tapestries the impact of this clash is all the more powerful.

Mark Lombardi, Global Networks BCCI-ICIC&FAB, 1972-91, 4TH version

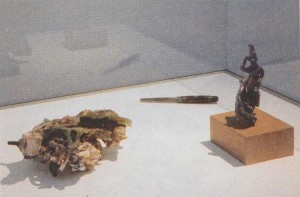

In the case of Vandy Rattana’s work Takeo (2009) there is a similar clash. It is a work from the series Bomb Ponds (2009) which consists of photographs depicting what seem to be just ponds in a landscape. In fact these are bomb craters which over time have been filled with water. Christov-Bakargiev has included Rattana’s photograph in the Rotunda section of the Fridericianum. Other works included here are Giorgio Morandi’s paintings of bottles and the bottles themselves. Also, archeological objects from the Beirut Museum made from metal, ivory, glass and terra-cotta that were damaged by shell fire and melted into completely new objects.

Vandy Rattana, Takeo Objects from the Beirut Museum + palette knife Etel Adman

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev nicknames the presentation in the Rotunda ‘the riddle’. The works there point to “a shifting of registers from the fictional sphere of the artwork to the world outside” [Artforum p.76]. I find this a crucial observation, useful when discussing how all the animate and inanimate makers of the world, to borrow Christov-Bakargiev s words, are ‘worldly’. Actually, for me ‘riddle’ does not go well with a distinction between the fictional sphere of the artwork on the one hand and the world outside on the other. ‘Riddle’ points to an inner life to which it is difficult to get access. It reveals itself a bit and closes up again, like the jellyfish in a poem by Marianne Moore:

A JELLYFISH

Visible, invisible,

a fluctuating charm

an amber-tinctured amethyst

inhabits it, your arm

approaches and it opens

and it closes; you had meant

to catch it and it quivers;

you abandon your intent.

The riddle in Rattana’s photograph is of course not solved when the history of the landscape is revealed. That is more a matter of necessary contextual information. Such information makes the riddle even more persistent. From now on I cannot separate the violent history from the innocuous image nor can I separate ‘picturesque’ from what I now know to be a bomb crater.

I wonder why painting is virtually absent in dOCUMENTA (13). Perhaps with painting it is difficult to gauge how the fictional world of the painting coincides with ‘the world outside’ when there is no helpful (anecdotal) background information about the image. Whether or not this is true, in any case the rare paintings at dOCUMENTA (13) seem to be instrumental for demonstrating specific connections rather than that they are left to be.

Margaret Preston Emily Carr

Preston, 3 paintings (left), Gordon Bennet, 4 paintings

An example is the room in the Neue Galerie in which the paintings of Margaret Preston (1875-1963), Emily Carr (1871-1945) and Gordon Bennett (1955) are hung. Their connection is obvious. Both Preston and Carr researched indigenous cultures, among other areas of interest, as sources of inspiration for their work. Gordon Bennett in his turn researched the imagery of Preston. His paintings depict Preston’s motifs but then on a much larger format: all his works are “after Margaret Preston”. No matter how interesting I find the contextual information behind Bennett’s paintings, the works themselves disappoint when I see them side by side with Carr and Preston’s. Carr and Preston seem to be presented together mainly because in their work they both made connections to ‘the world outside’ from an anthropological viewpoint. Bennett in his turn does arthistorical /anthropological research with Preston’s work as his material. I understand the connection between these three artists intellectually, but it does not work on the level of the imagination. There is no ‘riddle’ to it.

The presentation in the Neue Galerie does not do justice to the paintings of Carr and Preston. Perhaps a constellation such as: Gander > Preston > Carr > Kader Attia would work better because there is no cause for competition. My reshuffling would also solve a small problem I have with Gander’s work in the Fridericianum, namely the fact that the breeze blows through huge rooms that are practically empty. I simply miss the absent works. If anything, they could have been accomplices in Gander’s imaginative act.

Kader Attia’s (1970) installation: The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures (2012) struck me in the first instance as noncommittal and superficially aesthetic. However, I came to see it as a beautiful ‘riddle’, a bit like Marianne Moore’s jellyfish. The installation covers the floor of a large room. The lights are dimmed, the walls are lined with antique display cabinets such as one would find in traditional ethnographic museums. On display are “genuine artifacts from Africa” [GB p.38] and a slide show projection showing the deformed, mutilated faces of soldiers injured in World War One. Their deformed faces are the result of plastic surgery performed on them in an attempt to repair their faces. The genuine artifacts from Africa are wooden masks that have been ‘repaired’ too, by African restorers in attempt to keep the vulnerable material from disintegrating. The remaining genuine artifacts are large wooden sculptures, portrait busts made by contemporary African artists after the photographs of the deformed faces of the World War One soldiers.

Kader Attia

It was essential to know how and why those African masks were ‘repaired’: in the course of time they had been nailed and taped so as to stop the objects from falling apart. It was a restoration practice totally unknown in the West. African objects restored in this way simply were not exhibited in Western museums. This background information gave depth to Attia’s presentation. Copying the soldiers’ mutilations into contemporary art mirrors the borrowing of African imagery by early modernist artists in the West. Both practices are equally out of the context of their source material. The contemporary wooden portraits intrigued me in particular. I see them as the heart of Attia’s installation. I cannot make sense of them easily, taking all background information into account. It is their size being slightly larger than life, the offhand way by which they are chiseled from the woodblocks, and their resemblance to each other – each with a character of its own. The work opens and closes, like a ‘fluctuating charm’.

The Dutch poet K. Michel once made an analogy between poetry and the way mushrooms grow. Each mushroom has a delicate system of roots that is spread just below the surface. When something touches the mushroom above ground, tentacles begins to shake and tremble, touching others. You never know which tentacles were set in motion or how far the trembling spreads. That is left to your imagination. Strong works such as that of Attia, Aignier and Ryggen suggest that their rhizomes spread wide. Other works, however, spell out their connective pattern and leave little to the imagination. Maybe my expectations were too high or maybe I had simply anticipated a different Documenta and had difficulty adapting. But no matter what, dOCUMENTA (13) did channel my thinking to a new direction with ‘the worldly’ and ‘riddle’, especially, as new and refreshing reference points.

©Dineke Blom, September 2012

1 Quotes are from the following sources:

dOCUMENTA (13) The Book of Books: Catalog 1/3 [BB]

dOCUMENTA (13) Das Begleitbuch/the Guidebook:Katalog/Catalog 3/3 [GB]

Interview with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in Artforum, May 2012 [Artforum]

Interview with Carolyn Christove-Bakargiev, http://www.hatjecantz.de/index.php [HatjeCanz]

The poem ‘A JELLYFISH’ is quoted from The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore, Faber and Faber ed. 1958 p. 180