Mia Westerlund, Sculptures

Sculptures 1976-2012 at Betty Cunningham Gallery

As this survey through maquettes demonstrates, with Mia Westerlund it is either the body or its shell, that is, architecture.

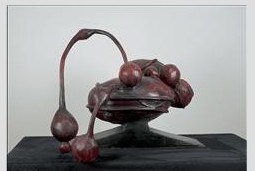

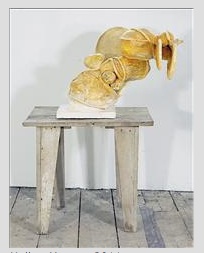

Let’s start with four new pieces that are not models—knockouts in a knockout show. These literally go to the heart of the matter, resembling nothing so much as aortal love knots. One of them, “Warts and All, “is even blood red. Two of Westerlund’s favorite shapes—the ball and the ligament—here combine in a pumping, flexing muscle. Although many aspects of Westerlund’s oeuvre employ a minimalist aesthetic—large holistic shapes often serially repeated (more of this later)—in these new pedestal-based forms she seems to allude to an earlier Abstract Expressionist mode. In imminent danger of toppling, they convey an asymmetrical precariousness that recalls Agostini, Roszak, Ferber , rather than Judd or Andre. ”Yellow Mange” has torqued itself into such leeward scoliosis it should surely overbalance. Thanks to this suspenseful cantilevering each rotation of the viewer reveals a completely new aspect. Like Proust’s Albertine, the works are more than multi-faceted; they are virtually different entities from one vantage point to the next. This is so much the case that a piece like “Double Probe,” with the same elements, color and finish as “Warts and All,” elides in memory with the latter, so that each can seem merely a different turn of the same gyre–this despite the fact that the former is centrifugal rather than centripetal and arthropod rather than anthropomorphic. Such is the degree of unpredictability that each work sets up.

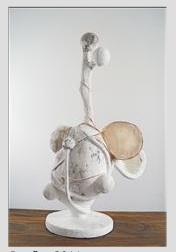

Another of the new sculptures, this time in a whitish finish, grows a neck, sprouts a pinhead and a prominent adam’s apple in a wonderfully funny figuration worthy of George Condo but without his hint of camp. Of this new quartet, only one seems less incarnate. It is an assumption, billowing up on clouds of its own ebullience. The blue is heavenly; the familiar balls turn cumuli with the help of sweeping directional curves. In essence, this is the body gone elsewhere. As with many of Westerlund’s titles, this one is a foregone conclusion. It’s called “Blue Madonna.”

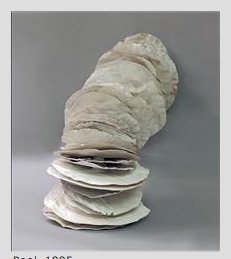

Migratory in their thrusting, yet thwarted by connectivity, the forms perch on the edge of orthodoxy with one foot in the land of the eccentric, the pre-frontal cortex of the surreal. “Hybridity” is a newish term in art discourse but Westerlund has been performing it forever. The recent works are a bit of a departure and so still anomalous. Yet her better known “primary structures” have always had nether parts. There are the wavering, organic, non-Euclidian “cuts” into the wall of “Bone” (pace Gordon Matta Clark ) and the delicate deckled edges of “Peel,” a variant on process-art “stacking,” Whereas Robert Morris’ felt mocks male potency with its limpness, Westerlund’s felt (dipped in resin) dances or flagellates itself into the ecstatic frothy lift-off of “Dervish.” There are the humps in the concrete striped rugs from the 90’s,whose hard materiality is in oxymoronic relationship with their depiction and whose stripes turn away from Stella et al to Tom and Jerry diving under the carpet to escape a marauding Spike.

Concrete has long been a staple of Westerlund’s materials pantry and the consequences have also been significantly cross-bred. There is a bluntness to concrete heightened rather than otherwise by the presence of the “hand.” An essentially industrial material is forced to reference the organic—no surprise there; this is post- Minimalist territory. But, as Westerlund uses concrete and stucco, there is no clear winner in the battle between body and architecture. Even works that are straightforward shelters manage to evoke physical distress in their allusions to the arid and sun-baked. Or conversely, a sense of cloistral, shuttered protection prevails, evoked by awning-like tongues cut out of the concrete walls. Other architectural enclosures, such as “Battenkill,” literally provide an oasis—a rivulet of running water passing around a spiral, another signposted post-minimalist form.

Architectural, concrete, often public, usually very large scale, Westerlund’s signature work has nevertheless insisted over the decades on what might be called the “feminine” side of these qualities. Situated in the context of her male peers’ puritanical rejection of image and allusion she clings to an isomorphic relationship between the body of work and the body of the viewer. (One thinks of Stanley Cavell’s sympathy for the philistine public who hesitated to walk on Andre’s metal tiles because they were felt to be, as all art is, an extension of the artist’s person. To walk on the floor sculpture was to walk on Andre himself, an act of hostility at which even the hoi polloi recoiled). Yet Westerlund has been overlooked in the recent revivals and surveys of feminist work now underway, Perhaps it is the very hybridity of her practice—which has been potent in eroding gender constrictions since the 70’s—that has so far distracted curators from including her contributions. Whatever the reason, this is an oversight that should be rectified. Westerlund is an important artist due for a major reconsideration, one, moreover, that would fill in the lacunae of recent history.

Ephraim Birnbaum