Vision is Elastic. Thought is Elastic

The most beautiful photograph I ever saw? I have described it here before. An exhibition of Sam Wagstaff’s photography collection at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford Connecticut: the usual canonized suspects are all there. Then, unannounced, at a distance across the room, scratching at the corner of ones eye, a small –4×6 maybe– black and white print. As one gets closer the crumples and creases show seemingly more than the image: cracked emulsion chipping off, a missing corner I think. It was a little too big to fit a wallet. More likely a photograph one would safeguard between the pages of a book, ones diary perhaps. It was a posed image. It revealed a man and a woman facing the camera: Bonnie and Clyde. Unlike the Bourke-Whites, and the Mapplethorpes of Wagstaff’s collection this one was anonymous. An authorless photograph, it constituted a gesture between the two pictured people. From him to her, and her to him: the camera as close to a love letter as it is ever going to get.

There is a commonplace that has been foisted upon us of recent decades that meaning is retrieved from the visual through words. That the one, the visual, is written over and through with the other, language –be it the language of thought, text or speech– is broadly speaking the conceit. A conceit, it often feels, pushed to the limit where language is framed as the redemptive coda to the mute, all but autistic, image. Layers of pre uttered and pre digested syntax, grammar and vocabulary hang in the room. Ghosts! There is no clarity of voice just a relentless heteroglossial squabble. Thus the names Faye Dunaway, Warren Beatty and Arthur Penn will forever haunt Bonnie and Clyde’s photographic love letter.

“Vision is Elastic. Thought is Elastic,” the current show at Murray Guy gallery wants to take a look anew at the collision between photograph and word or, more precisely in the gallery’s naming of it, camera and notebook. The show’s title comes from a journal entry of David Wojnarowicz. And anchors us as such within an art practice shaped by a dialogue between fragments of memory and wishes that many did not want uttered. The show “explores relationships between photography and activities of reading, writing, and note-taking”. One might commit to ones diary ‘I love him’ or take his photograph. It might be the same thing.

James Welling’s Diary of Elisabeth C. Dixon, 1840-41 and Connecticut Landscapes, is a series of images of the artist’s great-great grandparent’s diaries. Executed over an eleven year period, the work consists of small, (that is to say, the size of photograph one might slip between the pages of the aforementioned diary), black and white images of elaborate, cursive italic writing across diary pages. Leaves, blossoms or ferns are pressed between pages of said diary, while melancholy landscapes anchor the whole trying to stabilize a sense of place and time. Welling has worked over and through photography’s history throughout his career. The pressed flowers rhyme with his extensive repertoire of floral photograms, themselves echoing primitive photography’s cameraless image making. History and memory turn each other inside out and the diary and the camera emerge as devices for remembering even as illegibility clobbers the remembered. That the handwriting of Welling’s Grandparent is, if not illegible, then rather hard to read ties the hands of Welling, his grandparents and the current viewer behind their backs. What remembering is this that we grapple with? The Grandparental trip that the diary documents; photography’s pre-history or the difficulty of talking about how we remember, or, worse, remembering how we remember. Yes there is a looping reflexive collapse precipitated here. But Welling has for many seasons made hay with this posture of banality that conceals smarts and erudition.

In the grandparent’s diary writing –well, meaning actually– collapses into the act of making writing beautiful. While photography, in Welling’s oeuvre, as mnemonic act collapses into the limitations of barely getting out of the darkroom. Welling is demonstrating or perhaps showing rather than telling, that language is not going to explain anything. Language is not going to clarify images. Language becomes a smear upon the camera lens. There is, I have always felt, a depressive tone to Welling’s project. There is a wanting of clarity evoked, but a depressive recoil over the realization of its impossibility. Love letters would win no hearts if Welling were in charge and Bonnie would forget Clyde if Welling were the chaperone. All of which is why the Welling series might be the piece that best highlights the shows claims to symbiosis between photography and other notational practices. It is the symbiosis of the scar and the flesh when you are not sure which is which.

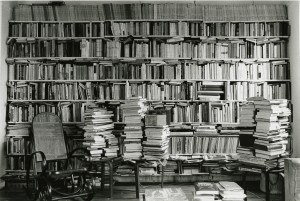

This opaque and deeply evocative lilt of language photographed recurs in Babette Mangolte’s image, Annette Michelson, Bookshelves on the Upper West Side in 1976. (1976). Many, many, words lined up in many, many books belonging to a founding editor of the journal October trigger a Benjaminian reverie around libraries and book collecting. Benjamin’s short essay speaks of the joys of collecting books. Of buying, borrowing and (pretty much) stealing them in the act of borrowing. Michelson’s book-spines, turned toward the viewer, tell us a few explicit stories; Kurt Schwitters, Beethoven, Jasper Johns are visible and legible. But mostly the books and journals are mute: just books and books and books and journals and…. The top shelf is loaded with what seems to be several hundred copies of a scholarly journal: it has the size, heft and un-glamour of a just such a 1970’s document. Something like the unvarnished matt bindings of New German Critique. Down toward the bottom many months worth of magazines turn narrow spines toward the camera while third shelf down, middle of shelf; those could be a collection of Paris Reviews. And then we run out of shelves! Badly so, with perilous, ready to topple, piles on chair and end tables. And then we have, or in fact do not have, the absent reader. Michelson’s empty rocking chair, at rest, blankly sits before us. Yet we do have her presence. Her depth of intellect and voracious cultural interest is the imposing personality marking the scene. Not depressive here, instead the clutter of read or unread books describe or diagram the owner’s intellectual idiom: the personal, intellectual contour of the friend of the smart Jewish girl with a typewriter, with whom –in 1976 as luck might have it– Michelson inaugurated a journal, a collection of words and pictures after all, that transformed New York cultural and intellectual life for ever.

Roni Horn’s Still water (The River Thames, for Example), 1999, presents as the work here with the most conventional relation of caption to image: i.e. caption will ground image, image will enhance caption. Except that in Horn’s work the image deliberately does not offer the goods to back up the caption. Opacity, murky depths, the still waters of the title, the swirling, Rorschach surface of water occludes that possibility. The captions are rich with information of historical events often baited with significant drama. While the images present an opaque sameness of moving water. Framed individually, torn from the flow of the river, different images allow different textures to emerge; an eddy here, a whirl there, or frothy pollution in this image. Colors shift, apparent depth changes. Superimposed by the artist upon this virtual abstraction is a history of events and psychological charges the river has borne. These events are of course only knowable through the narration by Horn. Nothing in the images evidences said happenings. She tells us of the suicides, say, that occurred here in this place. There is thus a whisper of the notion of charged place. Title your photograph ‘the chair where Salvador Allende died (see semiotext, Autonomia, 1980, p132) and sleight of hand/word imbues the scene with a whole other relational context. Importantly in the exemplary Allende photograph there is a bloody stain that draws one to puzzlement before the caption closes down the freely associative, promiscuous wandering. For Horn there is little formal excitement or referential enigma in the images and thus little incentive for aforementioned wanderings. It is this, which defines the moment where she makes her play. It is banality, a lack of melodrama’s visual evidence (or real political drama’s evidence) that turns the tables. It is a device kin to Welling’s photographs of barely legible words in that both coax language to tell little (or better, to falter in the telling). But Horn’s tactic hinges upon a site where language is tasked with this very responsibility: to tell, to explain. That captions ground images, and that images illuminate their captions has been the rule since monks scribed in cells. Contemporarily it is probably W.G. Sebald who has pushed the contrarian hand most fully toward overturning this maxim. For Sebald images sans captions drifted around the text fostering an inkling or two of connection to the pair of pages sunder current scrutiny. But it was in minding the gap between image and text that he fostered a certain autistic relation between the two. Horn’s captions brim with unhinged vigor, vis their images; indeed they seem hysterically expressive against the catatonic photographs. You could drown in one and swim in the other.

David Wojnarowicz, invoked as the catalytic Magus of this show, used much language in his notebooks and artwork too. He had a lot to say about a lot of things, about, for instance, social and sexual glues other than language; about the politicization of sexuality and about the terrorization of particular groups by the United States government. Wojnarowicz for sure saw, through the chimera of his Rimbaud romance, the misery of America circa 1980’s. In a passage from his memoir, Close to the Knives, Wojnarowicz laments, “I want to throw up because we’re supposed to quietly and politely make house in this killing machine called America and pay taxes to support our own slow murder and I’m amazed we’re not running amok in the streets, and that we can still be capable of gestures of loving after lifetimes of all this.” Indeed! Wojnarowicz’s practice was infused with the personal and the sentimental –as well as the political. And also with a knowledge of misery and want. His practice careened back and forth between the written and the visual sometimes seeming as if there were really no difference between the two. Which one might hope, in world where many artists feel no need to be defined by the consistent use of given medium, would be a norm. In, When I put my hands on your body, 1990, the piece shown here at Murray Guy, Wojnarowicz silk-screened onto a 36 x 47 inch photograph a text from his own prolific writing. Unlike Roni Horn, caption here scars the photograph and the latter loses clarity through its bruising by words: “If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth to this present time I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours I would.” A –probably, but I guess not necessarily– sexual, body-fusing mutes the question of language’s utility. Elsewhere it has been said that, we have language because we have bodies and bodies cannot be joined together, that “there are languages and language because there is want and want is misery”. Wojnarowicz’s work, choreographed as psychologically primitive, sexually total, and politically canny poses the possibility –or wish, or dream wish– for a relationship of merger where there is no need for language. Merger –if only (sigh)–trumps misery and want.

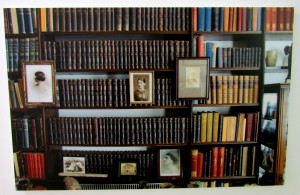

Freud is hiding somewhere around here. Joy Episalla will show us just where. And yes, he is of course hiding somewhere between the lines. 5 Women. Freud’s bookcase, London, 2011, is a medium format image of the Great Man’s bookshelves. Rows of books again, mostly, as can be gleaned from this image, on antiquarian matters and a glimpse or two of his antiquities around the edges of the tomes. It is a snap taken in Freud’s London redoubt. Post flight from Nazi book burners he was installed there as a kind of museum of himself. Appended to his shelves are photographs of five women important to his life and to the development of psychoanalysis: muses, mentees or both So who dare analyze the analyst? Or if not him then what it means that he places in close proximity to his beloved library and antiquities images of these 5 women? Episalla will, visually mind you, take a stab at it. Again it is charged space. The juxtaposition would mean little if were not the library of the guy who invented the Twentieth Century or at least a good part of it. But that disputable conceit that I spoke of earlier, “that meaning is retrieved from the visual through words” has come, in some quarters, to define his practice. It was in his dream book that he largely painted himself into this corner. That dreams, essentially visual phenomena, can only be returned to some semblance of sense through verbal interpretation was the picked mantra. But of course dreams also taught him and us about visual tricks, tricks of placement, juxtaposition. They taught us about a sense of uncanny presence. And it is the thrust of this show that there is something about proximity, about the placement and closeness that is crucial to describing and understanding the relationship between image and word. Like photographs placed on your bookshelf.

I would like to think Freud was also begging us to recognize a desirable muteness; an extra-linguistic form of relational encounter. The kind of thing that might crop up in say the pleasure of just having that image, in lieu of the actual person, of the loved other close at hand. It is important that it is one of the possible and frequent –though little mentioned in cultural studies use of psychoanalytical theory– effects of the analyst’s famous silence in the room that the two people there experience a quiet closeness, a relatedness. What I am referring to is not necessarily an analyzed part of the psychoanalysis. But then so much of said relationship is exactly that: not analyzed, just experienced. All this is well beyond the ken of meaning –meaning being a lackey of language– but Bonnie and Clyde new something about this, or, so I would again like to think. They new where to keep the memento mori photograph for safekeeping: no bullet holes!

Vision is Elastic. Thought is Elastic

Murray Guy Gallery

453 w. 17th street