Pages from a Magazine: CAMERAWORK at White Columns

White Columns allows itself the luxury –or the, delirium– of putting on shows with zero economic potential that graze in relatively obscure intellectual pastures. Pages from a Magazine: CAMERAWORK is the current wonderful example of this formula. CAMERAWORK was one of a number of left wing journals engaged (very much so) in the critical revaluation of cultural practice –the image world as it was sometimes known– in 1970’s and 1980’s England. Others were BLOCK, Control magazine, Wedge and ZG to name only the most prominent. In this show Mathew Higgs, White Column’s director, has pinned to the wall in an appropriately no-nonsense manner, his own collection of Camerawork magazines. Real artifacts –creased and a touch battered– displaying layouts of black and white photography which, more often than not, frames a special focus issue by issue. Thus we have a magazine on the wars in El Salvador or North of Ireland, an issue on nuclear weapons or one about racist gangs in London’s east end.

Camerawork was the spawn of the Half Moon Photography Workshop, itself the cousin of the politically immoderate Half Moon Theater which produced Bert Brecht and Dario Fo more than Shakespeare. And when they did do Shakespeare, it was Shakespeare very much as a ‘people’s’ theater. Half Moon Photography Workshop began as a cooperative, with all the political implications that word had in 1972. The members of both the theater and the photography workshop were affiliated with everything from left groupuscules to the squatter’s movement. CAMERAWORK ended, if not badly, then less well than one could hope, with the standard internecine splits in the left. Jo Spence, one of the founders, was expelled, sued the expellers, won, and with the settlement went on to publish PHOTOGRAPHY/POLITICS: ONE (and two, and perhaps more. I personally lost track after number two). By the time of the split Spence was already, also working with the Hackney Flashers, a “socialist, feminist photography collective”. (A fact that in many ways gives the feel of how different times were.) After Spence’s departure the magazine continued to be published by the original cooperative, sans Spence, for another 12 issues.

These were heady times when being a socialist artist, and arguing with other socialist artists was not a bizarre anachronism one would have to carefully explain to one’s students. Though Camerawork was not heavy with theory (at least in its early to ‘classic’ period) it was the case that dialogues about, say, the Althusserian reconfiguring of ideology ran alongside articles about the Workers Film and Photo League of the 1930’s, and ‘how-to’ darkroom tips to encourage people to take control of the production of photographs. In fact the magazine seemed, even if only sometimes, to have welded that elusive grail of the left, a concord between theory and practice.

For the first 19 issues the magazine proclaimed as if with the ardor of Charles Foster Kane inaugurating his first newspaper: “CAMERAWORK is designed to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas, views and information on photography and other forms of communication. By exploring the application, scope and content of photography, we intend to demystify the process. We see this as part of the struggle to learn, to describe and to share experiences and so contribute to the process by which we grow in capacity and power to control our own lives.’” By issue 20 all of the original members of the collective had departed. A palace coup had excised practice from the concord and the magazine sought to emulate the journal Screen for levels of linguistic density and quantities of syllables.

The pleasure of the White Columns show is that in an era when left politics has been expelled from most art practice (and replaced by a rush to make ever more pricey tchotchkes for Wall St parasites) a relatively modest curatorial project (this one will not be re hung for Venice or Kassel, guaranteed.) can remind us of the debates that used to shape what artists did as their daily practice.

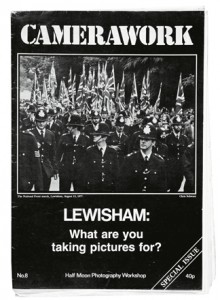

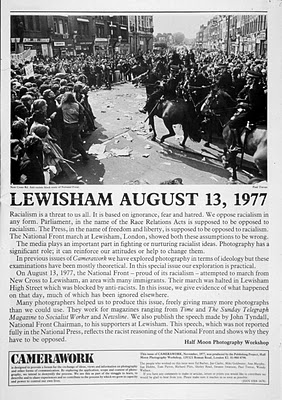

True, notions like ‘the democratization of image production and circulation’ can be a little difficult to wrap ones head around in the era of flicker and You tube. And tips on darkroom technique seem a little quaint next to my smart-phone. Yet it was not democratization as a quantity issue –as flicker etc seem to be– rather it is about empowering the unvoiced (no, not voiceless, the un-voiced) to be able to speak. Some old saw like speaking truth to power comes to mind. So when images appeared in Camerawork of, say, the anti-fascist riots in Lewisham, London the images were framed by the question, emblazoned across the front cover of the magazine, “What are you taking pictures for?”

It’s a play, a joke, a pun. It is what the average overpowered London cop of the time would have asked the photographer at the event. And yet it is also addressed to the wider question of why one circulates images. From and for what ideological position are you doing this shutterbug thing? (A question undreamt –or deeply, deeply, deeply repressed– in the silicone offices of Flicker et al)

And the title? Camerawork. Close the word space. Remove the Vaseline from the politics, fast forward past the anti Steiglitz jab and you run headlong into the semiotics of the day. Barthes to Sontag taking a photograph had been so withered by analysis of the power relation in shooting a photograph that the image sank into the messy context of words.

Ms Sontag reminded us in the opening of her text that we “linger unregenerately in Plato’s cave”. Squinting, as one must, to discern the true, truer or truest came to be about deciphering how images had been written over or through by language. And that was indeed the context that Camerawork created. Higgs’ curatorial choice –to pin the actual magazines to the wall– gives us this full context. Today we think of photography as less of a bounded, monolithic practice of visual representation rather we think images flow, circulate through the virtual, viral interspace of the web. In 1972 images circulated through the space of The Press and were battered by words and editorial power from all sides. The unglamorous stubble of racist speeches, unprinted by the mainstream press, (see image below) found newsprint as context for anti racist image making in Camerawork. It is good that White Columns has preserved the shadow of this important magazine.

What a delight to find this review description of Camera work at White Columns …

Thank you!