LEE UFAN & HANS-PETER FELDMANN at the GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM by Nick Van Zanten

The two main shows up now at the Guggenheim, a Lee Ufan retrospective and Hans-Peter Feldmann’s Hugo Boss Prize show, are quite worth seeing. Hans-Peter Feldmann’s work in particular seemed to give museum-goers pleasure, as I noticed many of them rubbing up against the walls of money and posing for pictures in front of it. Both shows are contemplative and offer exciting, visceral takes on the sublime, giving visitors quite a lot to think about without losing aesthetic strength. But what I’d like to talk about is the museum itself.

The Guggenheim (the building) is always fighting with the shows inside of it. Despite presenting artwork in a considered and unique way, and being built around that presentation, the spectacle of the building’s form always jostles for attention with whatever is inside of it. It’s torn between the competing demands of its creators that it be a “peaceful, elevating sanctuary” that imposes an order whilst also rejecting functionalism. It is so far from the functional, quiet white cubes that we are used to, and so loud, that the views and experiences of it always distract from the work even as they intend to aggrandize it. The non-objective work of Lee Ufan is just the sort of art for which the museum was intended, and the two fit together almost perfectly – yet it is still impossible to ignore the architecture. So I couldn’t help noticing a few things about it.

The Guggenheim is, as we all know, a spiral ramp around an open center, with the art on the exterior walls. These walls are divided into sections every 30˚, which more or less force curators to place works in their centers or at least create distinct tableaus within them. Viewing the work, you travel between each separate alcove, up or down the ramp depending on your metabolism, stopping and considering each one independently, almost always as a single image. Work is viewed by standing in the center of the alcove, taking in the whole of that section of the wall. The effect is much like the frames in a slide show or a film. The exterior of the building reflects the spiral of the interior, but with one difference: at the ground floor, the wall facing Fifth Avenue continues parallel to the street, then turns back, spinning into a second, much smaller spiral. This is because the long ramp gallery, a continuous line travelled along by visitors, is actually a filmstrip running along the guide parallel to Fifth Avenue, between the two reels. Each wall-separated module is a frame in the film, which is an image made by the visual art. And while this may sound like a mere metaphor for the museum-going experience, the second spiral proves that it isn’t – the filmstrip is unspooling from one reel into another, which is how projectors work; the receiving reel is the smaller spiral. The inside edge of the atrium even gets closer to the center the further it gets from the bottom (and so from the other reel that receives the film), replicating, like the rest of the building, a film projector. Naturally, visitors enter between the wheels, where the film would be projected out – in an odd way, this is a reversal of how films are seen and projected.

The building is that it bulges out as it goes up, giving it its distinctive tornado shape. Yet the open space on the inside is a regular cone, narrowing slightly as it goes up. Each of these is more aesthetically satisfying than their alternative, but the combined result is that the “ramp,” which might better be described as the galleries or the limit on the distance available for viewing each piece, grows narrower as one descends. Assuming that you start at the top, you find yourself pushed closer and closer to each piece as you travel. This mimics, in a longer form, the regular way of looking at art on a wall – starting out far off, and ever so slowing closing in on it, the eye working as the hand did, from general to specific. Wright has then forced us to follow a narrative of slowly and attentively approaching the work into the full museum experience. This doesn’t necessarily affect the art viewing experience since it’s on a larger scale, but the architect, having provided a narrative medium by making the museum a filmstrip, has also provided a narrative of art appreciation.

Neil Levine noticed that Wright had written on one of the drawings for the building “Taruggitz” – ziggurat backwards. This is, to some extent, what the building is, though I think its closer to a reversal of the minaret of Samarra than an upside ziggurat. Should it be either the point of prominence, the sacred center, would be at the bottom of the museum. It is worth noting that underneath the lobby of the rotunda – atop the ziggurat – Wright placed a movie theatre. Ground level is the best place from which to take in the full beauty of the space. But this sacred point offers no view of the artwork. Thus we can safely say that two systems are acting at once – the reverse ziggurat of the space, designed by a the architect to glorify himself and his work, and the filmic system of viewing the actual work.

Abstract painting, which the museum was designed to show, has an odd relationship to film because painting is composed of images that defy time and narrative and exist in absolute stillness. Film, meanwhile, is composed of images, but these are defined by their positions relative to overall time and become, in the eye of the viewer, not a series but a continuous, changing image. Before film and photography existed, paintings would tell a story by being hung and viewed in sequence, an idea that lead, by way of photography, to the invention of film.

Wright also placed eye- or lens-shaped motifs in the building (for instance in the fountain) and divided the whole rotunda, most obviously the dome, into twelve sections. If looking up at the dome one sees a clock, then travelling through it, down to the bottom of the ramp and a sacred nadir at the tip of the reversed ziggurat, one also travels its perimeter, moving through time in relation to the fixed marks on the roof like the hands of a clock do.

It is hardly surprising that the museum is designed to place its art in a single possible narrative, since this is what any visitor necessarily experiences. Yet it is remarkable how aware the building is of the implications of that – that by creating only one line of images that viewers can see in sequence, the building is turning those images into a film – while curators and artists struggle to take it into account and create the filmic exhibitions that the space is demanding.

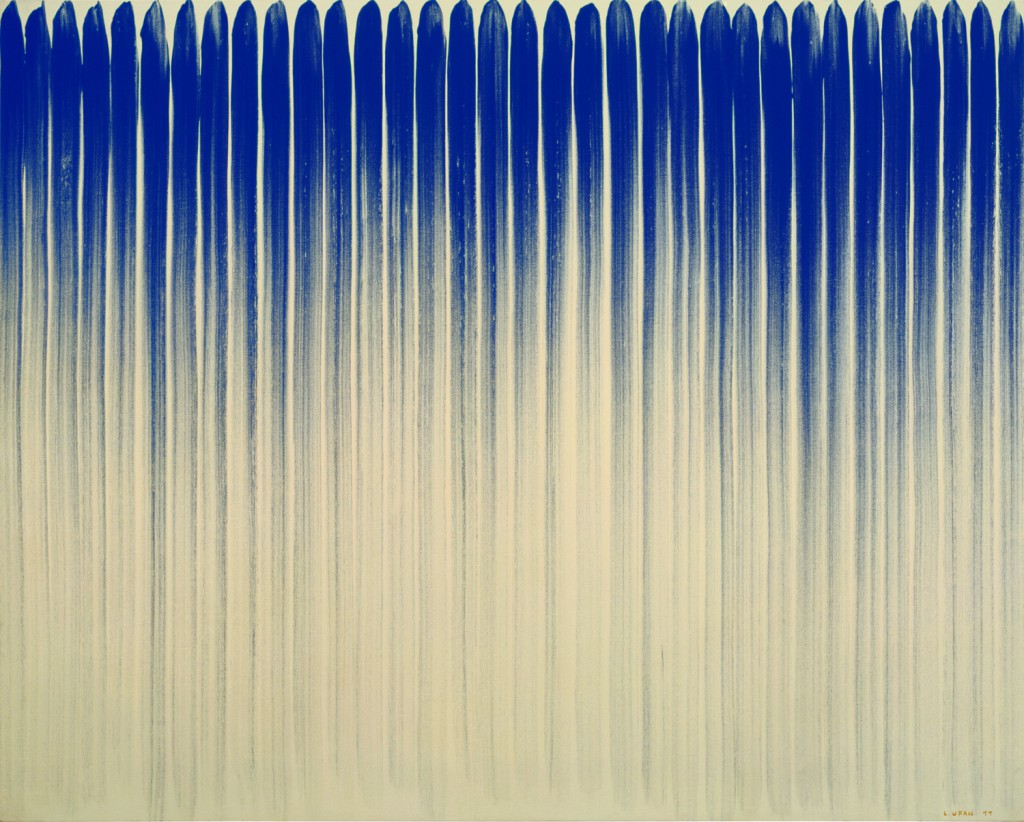

The Lee Ufan show works well with the space, though. The isolation that each alcove gives to its contents compliment that quiet, meditative manner in which Ufan’s pieces were made and in which they should be viewed. The narrative of the show works well, though I did find myself reversing directions more than once. But by placing each piece in its own film frame, and therefore in its own space and time, one can experience them much more profoundly than might be possible otherwise. The final room of the exhibition is in the annex (as is the Feldmann), and the pieces suffer from not having the same sort of space which succeeds so brilliantly in the rotunda, where viewers are put in a proper frame of mind for each piece, and can face away from the atrium without feeling that they are missing a thing.