Bellini’s Protestation

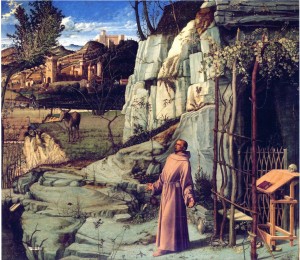

I recently found myself at The Frick Collection in New York (having temporarily escaped time and gravitational confines), where I was captivated by ‘St. Francis in the Desert’ – also called ‘St. Francis in Ecstasy.’ The artist Bellini raises endless questions for this visitor -I found some background on the protagonist of the picture:

Trained in chivalry (courage, honor, justice), St. Francis, and subsequently all Franciscans, take a vow of poverty. Their calling requires a self-regard of humility and restraint; they are the equal of others or of lesser stature.

I claim no training in the terrestrial cult of art history. I have read about its methods in the journals of artists that are preserved in our ontologies. Nonetheless, as a hypothesizer, I will attempt to cast a brief threadlight into its significance.

Generalizing, it seemed to me that features of the composition could be considered ‘Franciscan’ in style as it reflects restraint. Inwardness is a trait I have studied, and the saint appears to be addressing the immaterial in his surroundings, something utterly modest, even poor. He is unencumbered. With so few possessions, I surmise that privation is a requisite for the circumstance he seeks. In our age, his divestments would be considered very advanced. The picture is graced with an array of singularities – a book, a lectern with death’s head, a sole foliated tree, and a distant citadel that appears unoccupied.

Long centuries have catastrophically changed the earth since this picture was made. The green quilt of its natural cover has been ravaged by timbering, and the wind howls in channels through these hollows. Though over-populated now, the picture shows that empty stretches of desert, rock, and hillside once prevailed and supported simple life; a landscape in which contemplation and loneliness were still possible. (I have always wondered why loneliness was considered so problematic. Now we think of it as a state of being that is hopelessly lost to us. We study it in workshops on psychological archaeology. And we yearn for it, dream about it when we have a ration of sleep in which to dream.)

How is the picture timed? Hard to determine, because day to night is so fluidly reversible in my experience, and few have the luxury of slowing down to observe subtleties. Who can now truly understand the suspense of this pacing? In my world – none – except as an archaic stage of human development.

The picture suggests what used to be called sunrise (according to a cinema made to explain the picture’s meaning), but dawn – as a white suffusion in the sky – is a concept, metaphorical. It no longer exists phenomenally. When the saint’s chastened transformation begins he is positioned ethereally, gazing up and beyond the frame of the picture. The world around him trembles to reinforce his pose. He is ready to test the precipice.

When we join him, the seraph (not depicted, but a kind of fantastic flying creature typical in Christian imagery) has already marked his palms with the miraculous stigmata. Blink, and time, as a function of light, changes, appears burnished, older, humbled, and chooses to attach a shadow to St. Francis alone. He is allowed to age. The scene is full of detail but conveys the minimalism of what people on earth called solitude.

Illumination is crucial to its deep meaning, but difficult – if not impossible – to characterize or keep still; perhaps it is simply a reflection of Bellini – a natural Sensitive, with a prodigious gift. It is at once an idea, but also a subject, an agency. It has no technological explanation. Considered as a radiance, it seems to emanate from St. Francis – in the softly painted folds of his ochre garment (though a cave of darkness follows him). His dress recalls the color of a place called Tuscany – and the Appenines (mountains I think) – as if the figure has been mined from the mineral grandeur of these ancient hills. In my studies, I came across some paragraphs by a writer named Albert Camus, who, after a second visit to a place called Italy in the year 1937, described this light as “ . . . a dark flame . . . that Italian painters have raised from the Tuscan landscape as a lucid protestation…” (1) I am fascinated by this wondrous possibility.

St. Francis is the color of clay. His strand is the color of earthsea – green and blue. The rock surfaces are liquid – they wind in curves, leaving tide lines – a theology of water in what is now a burned world. Transubstantiation of matter is brilliantly captured, the conversion of substance, flesh and stone, and its consecration. Is this really the desert? Who can answer? Or, as the first title implies, a bygone state called ecstasy, possibly summoned by the glorious play of matter and light in a paradise lost, or the ecstasy of the communicant.

How this great and treasurable illusion of the past will effect me, I do not know. Except singularly contained on a square wooden easel, an island in a circular room isolated from everything else, and coming toward me at a perfect height – I wanted to enter, to step into this enviable seclusion. To be lonely and transformed.

Halo Jones, Year 4952

(1) Albert Camus, “The Desert,” (to Jean Grenier), 1937. I came across this faded yellow typescript (the kind terrestrial writers used in the twentieth century), in the files of a citizen who called herself a critic.